INVESTMENT

How to set an investment strategy

A robust investment strategy has to be linked to your financial goals and, crucially, the extent to which they are flexible.

Within the financial advisory industry, a key input into investment strategy is the risk attitude questionnaire. If you want to see what these are like, this is quite a good one. The idea is that by finding out how you typically react to gambles and investment volatility, you can determine the right risk level, and consequently asset mix, for your portfolio.

While risk attitude questionnaires are not a complete waste of time, they pay insufficient attention to the relationship between the assets and the objectives. In the realm of personal financial planning, risk is all about the probability and extent to which you may not meet your financial goals. In this context, Nobel Laureates William F Sharpe and Robert C Merton emphasize the importance of matching investments to desired expenditure when designing an investment strategy. Indeed, the attempt to guarantee fixed payments with a risky portfolio is at the heart of what Merton calls the ‘crisis in retirement planning’ (and as an aside was also behind the dire deterioration in corporate pension scheme finances after the mid 1990s). Instead, he says we should adopt a ‘liability-driven strategy’ where the investment strategy is driven by the goals we set and the extent to which they can be adapted.

He’s right.

So how, in practical terms, do we go about this? Here are seven steps to help you. These are most relevant to people in the building wealth or moving on stages of professional life. If you’re starting out there’s a strong argument that you don’t need to agonise too much about investment strategy, but instead can keep things pretty simple, keeping your investments overwhelmingly in higher risk asset classes.

1. Define and quantify your goals

Get a large piece of paper and draw a line on it, representing your future life. Along the line, mark key dates and associated financial goals: milestone birthdays or educational requirements for your children; your hoped-for retirement date or career change; the point at which you want to buy a second home in Spain; the spectacular silver wedding present for your spouse (what, you missed it?); and so on.

Next, for each goal, estimate how much money you will need to accumulate to meet it. The biggest single (and perhaps hardest to estimate) amount is what you’ll need to fund your ongoing lifestyle once you transition from your main earning career. You can find help in previous articles on figuring out how much is enough, and the fund you’ll need to provide that.

At the end of this exercise, you should have a time series of boxes with different associated financial amounts.

2. Assign a level of flexibility to your goals

This is perhaps the most important, but often missed, step. You need to define the level of flexibility in each of your goals. Some will be completely inflexible in timing and amount: for example, supporting children through university. Some will have some flexibility in timing or amount: for example, the cost of a holiday home might be relatively fixed but you could defer it for a year or two, or even forego it altogether if necessary.

Perhaps most important is to establish the flexibility in your long-term income needs once you leave your main earning career. Understanding how flexible you can be will become increasingly important in terms of managing your investments as you approach retirement. So think about the level of income that you really feel you cannot do without as well as the level that you would ideally prefer to have. For successful professionals it’s likely that your targeted level of expenditure is at least two times the level on which you could have a comfortable retirement.

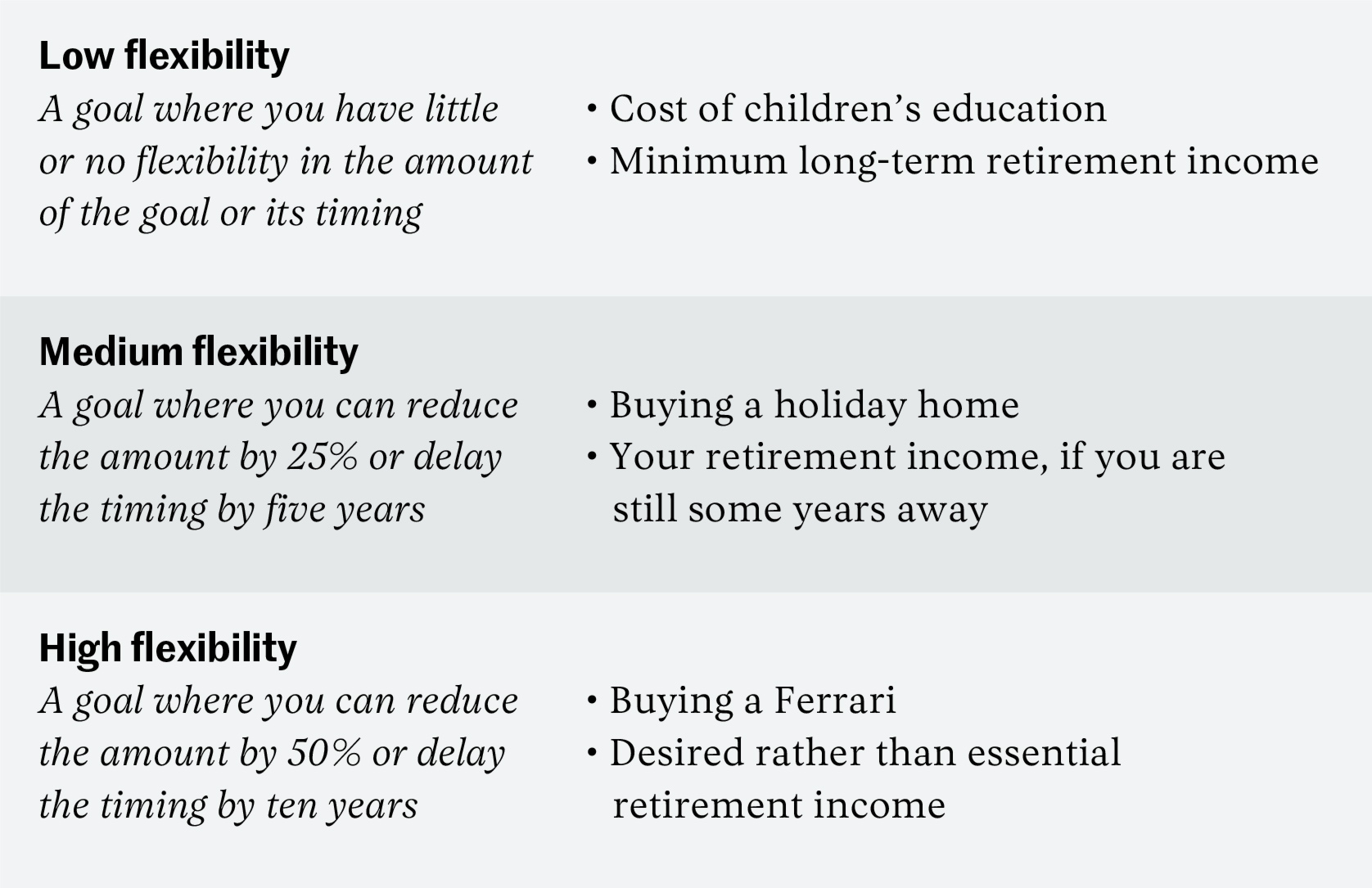

Think in terms of three categories.

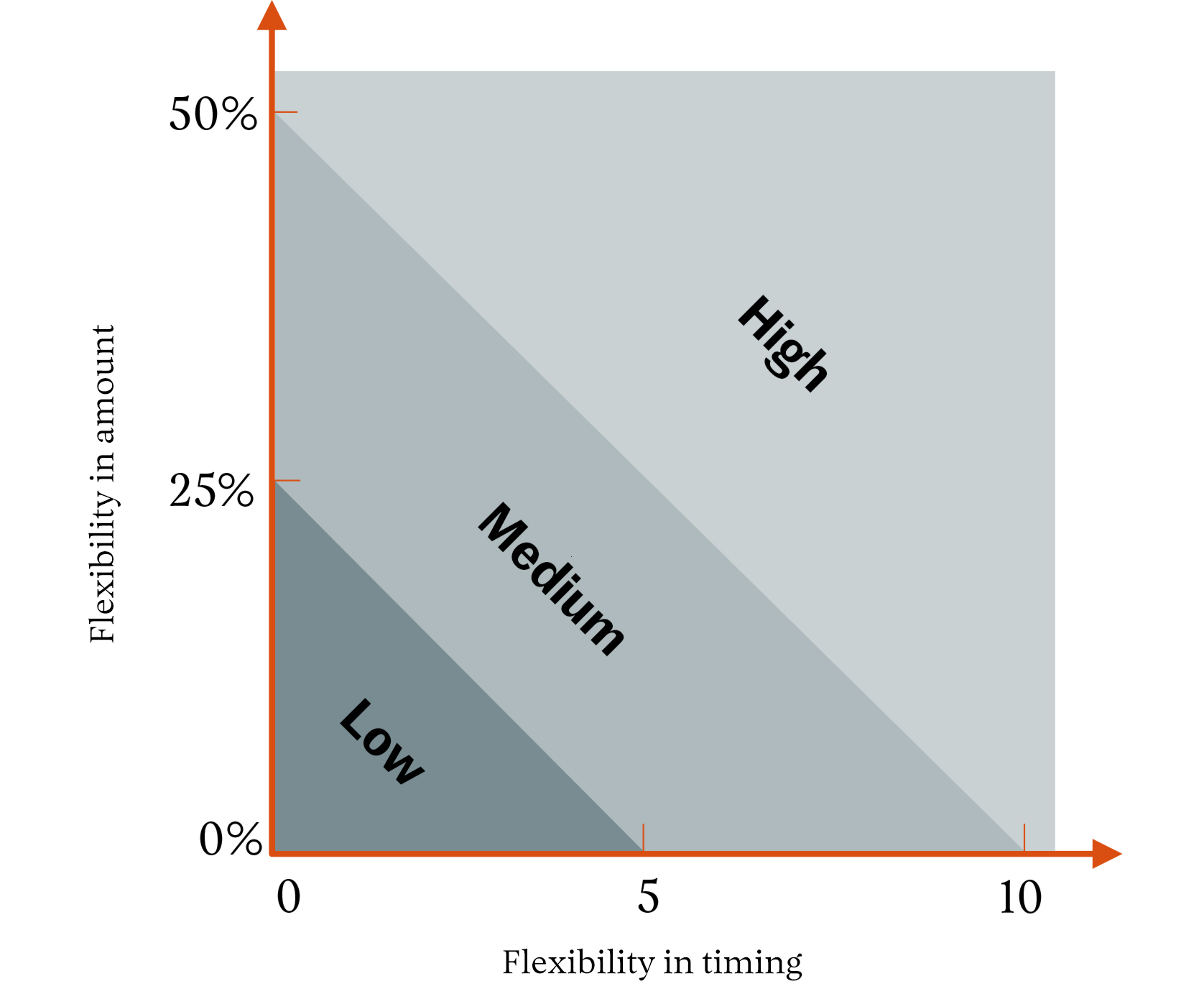

Within each category there’s a trade-off. So for example, a goal where there’s no leeway in timing but you can reduce the amount by 50% would still count as high flexibility. Similarly, if there’s no ability to change the amount but you can delay the goal by 10 years that is still high flexibility. Here’s a picture to help see how different levels of flexibility in amount and timing lead to an overall flexibility categorisation.

3. Match investments to categories

You’ve probably figured out by now where this is going. Following the principle of matching our assets and liabilities, we can define our first-cut strategy as follows:

- Low flexibility goals need to be matched with low-risk assets like cash and bonds. If you really cannot delay the timing of a goal or reduce its amount, then you can’t take risk with the investments.

- High flexibility goals can be matched with high risk investments like equities. The guiding numbers weren’t just pulled out of a hat. Equities can fall in value by half within a year or two. They can take 10 years to recover their value (occasionally even longer). If your goals are similarly flexible, then your investments can be too.

- Medium flexibility goals sit in the middle. A balanced strategy (for example a 60/40 portfolio of equities and bonds) will work well. Such a portfolio will typically not fall more than 25% in a year and will normally recover within five. With bond yields so low, some experts, like Jeremy Siegel, believe that 60/40 should now be replaced by 70/30 or 75/25.

4. Allow for your human capital

If you have 10 years or more of your peak earning career ahead of you, then you can consider shifting all or most of your goals up a flexibility category. This is because your high level of human capital, plus flexibility about how long you work, can allow you to take more investment risk. This intuitively obvious fact was demonstrated theoretically in a 1992 paper by three titans of the economics of personal finance: Zvi Bodie, Robert C Merton, and William F Samuelson. Working an extra year or two is likely to be enough to offset early losses on your portfolio. Moreover, when making continued investment contributions over time, a market fall provides the opportunity to invest at lower prices which partially offsets the losses made on your existing portfolio.

Indeed, if you’re a professional just starting out in the high earning phase of their career, you probably don’t need this process. In most cases the high levels of human capital plus the flexible or unspecified nature of many of your goals will make a higher risk investment strategy the default and simplest option.

5. Test affordability

With luck, you’re already spending less than you earn and have a good handle on the financial surplus that you have available for investment each year. You’ll also have some level of accumulated pot. Now you need to see whether this level of investment, coupled with the investment strategy designed under step 4, is enough to meet your goals.

This is where cashflow modelling can come into its own and a financial planner can help with this. However, most cashflow models are based on a single asset mix rather than one that matches investments to goals. And too often it’s a bit of a black box that spits out an answer without creating much insight as to its inner workings.

So you can do this yourself. The simplest starting point is to take each goal and allocate a portion of your existing assets against it. Sometimes this will be obvious: existing cash deposits matching a short-term education expense, for example. Then assume that you’ll seek to bridge the gap between where you are today and each of your goals on a phased basis over the remaining timescale for that goal. You might decide later to change this order. If you’re very confident in your future career security, you might invest in a higher risk way initially, with the idea that you’ll meet your low flexibility goals out of future income. Or if you’re concerned about your career security you might do the opposite. In most cases, in the world of personal finance, the extremes are unhelpful and so some balance in pursuing the different goals will make sense.

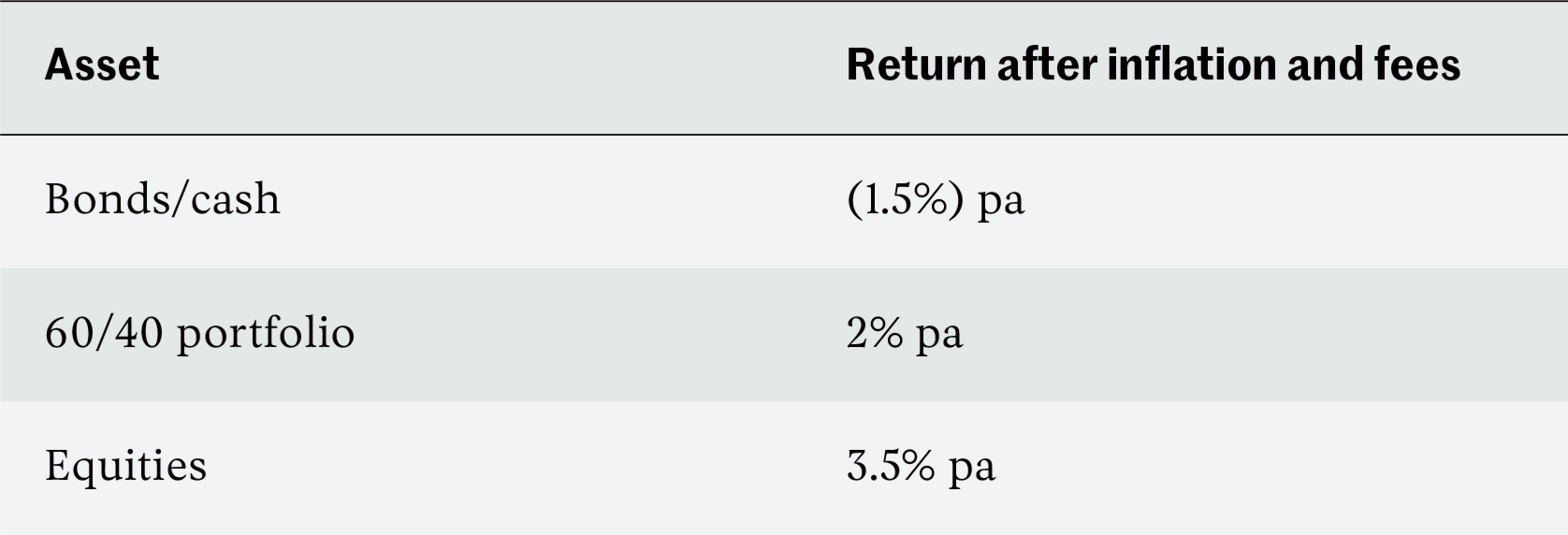

When figuring out whether you’ve got enough to meet your goals, you’ll need to make an assumption for each category of investment. It’s very difficult to know what assumption to make. I explain elsewhere why I tend to use the following real growth assumptions (i.e. returns relative to inflation):

Don’t feel you have to do the sums with painstaking accuracy. The uncertainties over future investment returns (and everything else life may throw at you) will likely swamp any approximations you make. Indeed, a simple planning hack is to ignore investment returns altogether and work in real terms when assessing whether you will meet your goals. This is equivalent to assuming a zero real return on investments, which is a conservative (probably a 75% chance you’ll do better than this), but not ridiculous, simplifying assumption.

6. Iterate your plan

If you’re lucky, it’s all worked out first time and you can easily meet your goals or better. If not then you’ll need to adapt. There are four ways to do this:

- Reduce your goals, so that you don’t need to save so much.

- Increase the flexibility of your goals so that you can take more investment risk.

- Increase what you plan to save, either by increasing the yearly amount or the time for which you’ll continue in your main earning career.

- Increase investment risk without changing your goals, but instead accept a probability that you will fail to meet your minimum goals.

The last is generally not to be recommended. Much better is to figure out whether you are really being as flexible as you could be in how you’re setting your goals. If you can be more flexible, you can benefit from the higher return (but higher risk) of a bigger allocation to equity investment.

7. Sense check and scenario test your plan

Rules of thumb exist for a reason: they reflect the broad pattern of experience. So it’s worth checking your final investment plan against them. Based on your analysis, tot up how much you have in equities and bonds/cash across your strategy and how this could change over time. If you’re 10 to 20 years from retirement you should probably have at least three quarters in equities. If you’re within five years of retirement you should probably have between a quarter and half in bonds. If you’re way out from these metrics, or miles away from what a risk attitude questionnaire suggested, there may be a good reason. But it’s worth reflecting whether you’ve really got it right.

Then dream up some scenarios and figure out how your plan would react to them. Remember that risks come in many shapes and sizes. Here are some ideas:

- A 50% fall in equity markets tomorrow.

- A 50% fall in equity markets the day before you retire.

- A burst of inflation and a sharp increase in interest rates.

- A burst of deflation and a sharp decrease in interest rates.

- A large emergency expense.

- An unexpectedly early end to your high-earning career.

- Death, illness or divorce.

- A platform provider goes bust.

Thinking about a wide range of risks will often lead to balance in your plan. Taking any extreme position will tend to create higher returns in certain scenarios but at the cost of high risks in others.

Based on any insight from these scenarios, return to step 6 and iterate your plan again. Once you’ve done this to your satisfaction, congratulations — you’re done!

What do we mean by equities and bonds?

For the purposes of this article, I’m somewhat glossing over the details of what we mean by equities and bonds. I’ll leave the finer points of different investment approaches to another day. But a couple of comments for now.

By equities, I’m mainly thinking about a globally diversified, low-cost tracker fund invested across the world’s stock markets. For most successful professionals this will be the most effective choice. But it needn’t be that. You may instead prefer active management. You may have views on the right allocation across different stock markets. You may be a devotee of factor or risk parity investing. You may even choose property investment as your growth asset of choice. Here I’m just talking about a class of higher growth, higher risk investments comparable to a diversified stock market investment.

The question on bonds is a bit more subtle.

For very short-term, low flexibility goals, the relevant asset is cash deposits.

For matching a long-term minimum level of retirement income, the relevant matching asset is either an annuity, a ‘bond ladder’ of index-linked gilts or a long-dated index-linked gilt fund. A bond ladder is a series of bonds with maturity dates spanning the years over which you need the income and hence matching it as precisely as possible. For example, if you plan to retire in 2025 and live for another 40 years, then a bond ladder would be a series of index-linked gilts maturing between 2025 and 2065 to meet your income needs. For your low flexibility goals, the bonds are used to match as precisely as possible your income requirements, thereby reducing investment risk as much as possible.

For your medium flexibility goals, matched by a 60/40 portfolio or similar, the bonds play a slightly different role. Here they are not used to match specific low risk liabilities. Instead, they act as a diversifier to reduce the volatility of this portion of your portfolio. Their job is to fall less (or even rise) when equities crash. The cost is that they will provide a lower return than equities when markets are booming. So they reduce the volatility of your portfolio, at the cost of some expected return. For this purpose the natural investment is a bond fund to sit alongside your equity fund (or even a multi-asset fund that combines the equities and bonds in one). The best diversification benefits, particularly in down markets, are provided by long-term government bonds. But your fund may also include some shorter dated bonds and corporate bonds. This isn’t something to worry about until you get to a greater level of sophistication in your strategy.

Worth the time

If there’s one key point I’d like you to take away from this article, it’s that you must consider your investment strategy alongside the flexibility you can have in the amount or timing of your goals. Challenge yourself on whether you can have more flexibility in your goals so you can take more risk in your investments. But don’t think you can do the latter without the former — that can cause build up of significant tail risks that can lead to the complete breakdown of your plan in a stress scenario.

Setting an investment strategy well is something that does take a bit of time. Like most good things in life, you can’t get it without a bit of effort. But a well thought through and resilient strategy will help you to create the optimum balance between maximising your financial opportunities while minimising the risks you really care about. This can help you sleep at night, while making the most of your career success.

It’s well worth it.

Important

Nothing in this article should be taken to represent financial advice. It is generic commentary based on typical circumstances and not tailored to your own situation. If you’re not sure what to do, you should take financial advice.