TRANSITION

Have I got enough?

The 4% rule is a simple way to figure out if you’re financially secure. Frequently criticised for being naive and out-of-date, for successful professionals it’s a pretty good guide.

It’s a first world problem I know, but the move from earning a regular salary to living in whole or part off your savings can be an anxious one. How do you know if you’ve really got enough? A pot that looks healthy enough if you assume historic investment returns doesn’t look so great if you believe doom-laden predictions for returns based on super-low interest rates and overvalued markets.

A famous rule of thumb for determining whether your pot is big enough is the so-called ‘4% rule’. The idea is that if you start with a pot of £1m at the beginning of retirement, you can draw an initial pension of £40,000 (4% of the pot) and increase this in line with inflation each year. If you do this, your pot should last you at least 30 years, the length of the typical retirement.

The 4% rule is based on the work of legendary retirement scientist William Bengen and subsequently supported by several iterations of the so-called Trinity Study of retirement pathways. The basic idea is that even during the worst periods we’ve seen in history, investment returns would’ve been good enough to let you withdraw 4% a year from your pot for 30 years without your money running out. So 4% is called the ‘safe withdrawal rate’. Take your money out any faster and your pot could run out before you do. (An important detail is that the 4% withdrawal is based only on the initial portfolio value at the start of retirement — the withdrawal amount then increases each year in line with inflation, regardless of what happens to your portfolio.)

Naive and out-of-date

The 4% rule is a favourite of the FIRE (financial independence retire early) community as a way of figuring out when you can give your boss the finger. Turning the rule upside down, simply take your annual living expenses and multiple them by 25, and that gives you the pot you need.

But the rule is coming in for quite a lot of flack. As it applies to the successful professionals I work with, the rule can validly be subject to the following criticisms.

The analysis ignores fees. Yep. Validation of the 4% rule is based on historic investment returns without advisor fees, taxes and the like.

The analysis is based on US data. Another valid criticism. The US stock market was the clear winner over the last 120 years with returns, according to the Credit Suisse 2020 Yearbook around 1.3% pa ahead of the global stock market. It’s unclear whether it can repeat the trick. In any event, most people outside the US invest more broadly than just the US market.

The analysis is based on a 30 year retirement period. This is a major issue for successful professionals. For a couple looking for financial freedom at 50, there’s roughly a 1 in 10 chance that one of them will live to 100. That’s 50 years, not 30.

Future investment returns will be lower than in the past. Given super low interest rates and heady market valuations, it’s asserted that modelling anything based on history will be hopelessly optimistic.

Should it be the 2% rule?

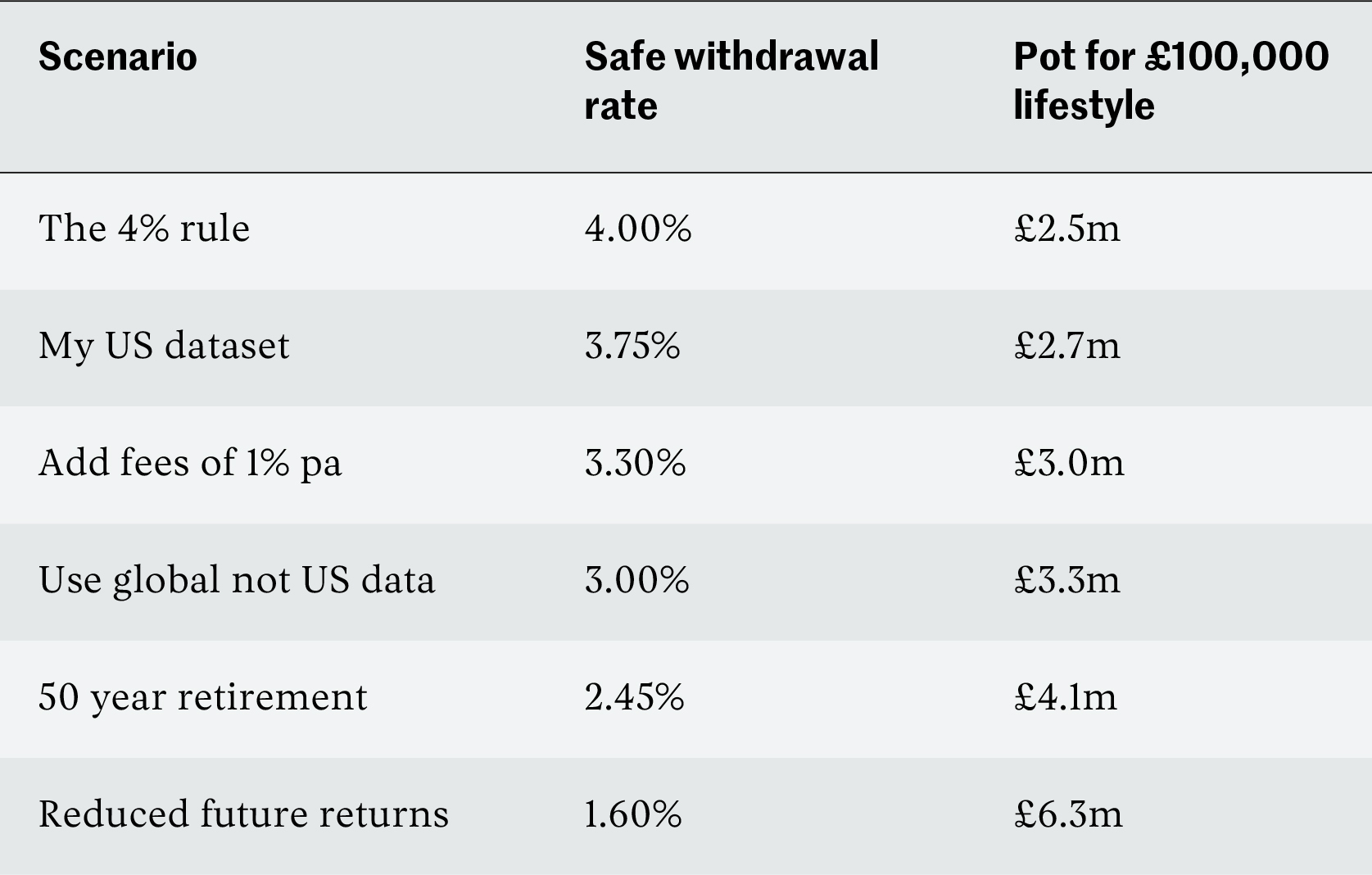

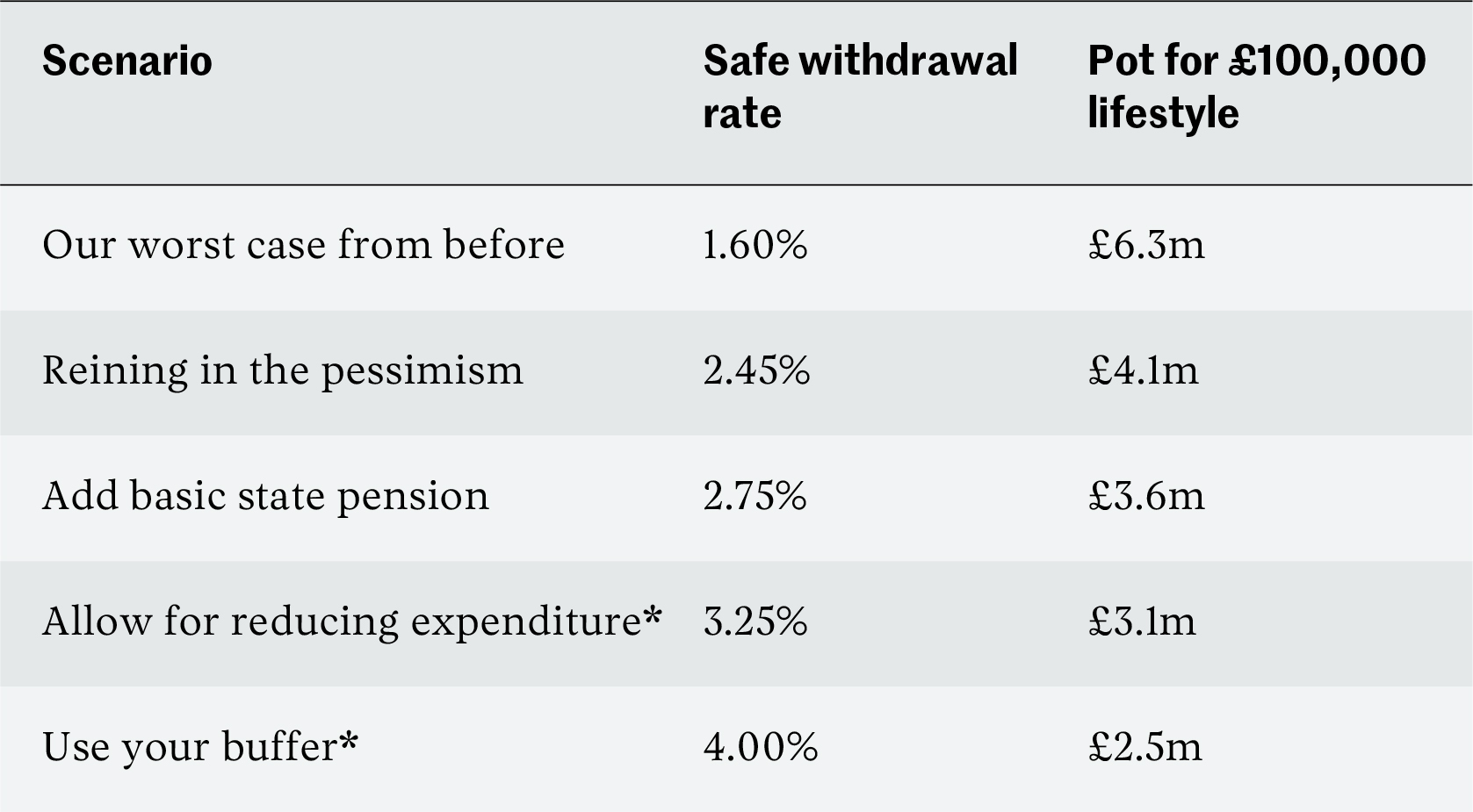

So let’s look at the impact of addressing each of these criticisms. The table below looks at the safe withdrawal rate, based on history, assuming a portfolio of 60% equities, 40% government bonds. I also show the fund needed to support a £100,000 a year lifestyle. I pick this number because it’s a round number and it’s not untypical of what people I work with say they want to aim for. Whether they really need anywhere near that much is another question, which I’ve considered elsewhere. You can easily scale the numbers up and down to the level of your own expectations.

Each dataset varies slightly – for my own US dataset the safe withdrawal rate was 3.75% rather than 4%.

For the scenario of reduced future returns I’ve scaled back historic US equity and bond returns by 3.6% and 1.9% respectively, to give prospective real returns of 3% and 0% respectively. This broadly equates to current real long-term bond yields and equities outperforming bonds by around the historic average.

These are big differences. Maybe it should be renamed the ‘2% rule’ not the ‘4% rule’? To get from £2.5m to £6.3m is quite a few years of hard work, even for a high-earning professional.

But here’s the good news: I hope to persuade you that the extra work may not be necessary and the 4% rule remains a decent starting point for successful professionals.

Reining in the pessimism

Having made you fear you’ll need to work forever, I now want to bring you back one step at a time to sanity.

First let’s look at the assumption around reduced future returns.

Prospective real bond yields are low, but low real returns on bonds are not unusual. Real returns on 10 year US Treasuries were around zero or negative for every 50-year period starting from 1929 to 1940. But during these periods real equity returns varied from a low of 4.6% pa to a high of 7% pa. So it’s overly pessimistic to assume that future long-term equity returns will be low just because bond yields are. And while US equity markets do look close to the limits of historic valuation levels, this is much less true for other international markets. And even in the US equity markets have been this expensive in the past: in 1929 and in the dotcom boom of 2000, both of which are included in our historic dataset.

1929 is a particularly interesting comparison with today, because not only were real bond returns effectively zero over the next 50 years, but the CAPE (cyclically adjusted price earnings ratio) on the US market was almost exactly the same as today suggesting similarly overvalued markets. It made for a rough few years as the stock market crashed, but in the end an investor could’ve withdrawn 3% a year without running out of money. By the same token, an investor retiring in the mid-1960s experienced three bear markets and runaway inflation in their first two decades, giving zero real returns on bonds and equities. The damage caused by the bear markets early in retirement are what makes this scenario the one that defines the minimum withdrawal rate of 2.45%.

Remember what the safe withdrawal rate does: it figures out how much you could’ve taken out in the worst scenario in history, not an average scenario. Our historical period includes the great depression, two world wars, collapse of the gold standard, the dotcom crash, the financial crisis and COVID. By shifting the central return assumptions to align with a lower return future, we’re creating new downside scenarios that are much worse than the past. Under my pessimistic shifted assumptions, one in six scenarios of 30-year equity returns and one in three for bonds are below the lowest ever actually experienced in history. Should we really assume that the future is going to be so dramatically worse than the past?

If you’re prone to catastrophising when it comes to investment, as I’ll admit I am, your problem is that there’s virtually no limit to what you can realistically assume (have you prepared for alien invasion yet?). Risks that are outside the boundaries of past experience shouldn’t be discounted, but perhaps need to be dealt with in a different way. Building an ever larger war chest addresses an uncertain future risk with a very certain current cost: less freedom and a delay to your life plans. Instead, if we’re concerned about them, we need to handle these extreme events through two devices. First, securing a minimum level of retirement income through use of a passive holding of long-dated government bonds and second considering how we’ll adapt our plan if that doomsday scenario emerges. I’ll return to these in a future article. But for now, I think we’ve concluded that assuming scenarios fantastically worse than in the past probably isn’t that helpful.

Adding the state pension

Most of us wouldn’t want to be left relying entirely on the basic state pension, but at the same time it makes a very useful contribution. For couples with a full National Insurance record it’s a little over £18,000 a year. (Hint: check your state pension forecast and if you’ve got a gap in your National Insurance record then make payments to plug it. Some better off couples are missing out on credits by not claiming child benefit to avoid a tax hassle as opposed to claiming it, then opting out.)

Currently payable from 67, the basic state pension can add between 0.25% and 0.5% to your safe withdrawal rate depending on the size of your pot.

Recognising your spending patterns

Most retirement planning assumes that your expenditure will increase in line with inflation each year. Indeed, one financial planner once modelled my scenario assuming increases 2% ahead of inflation. But the data shows the opposite: expenditure falls in retirement by between a quarter and a third between the peak years of 50-60 and 75 onwards. A good summary of the research can be found in the white paper produced by Abraham Okusanya of Timeline or in his book Beyond the 4% Rule.

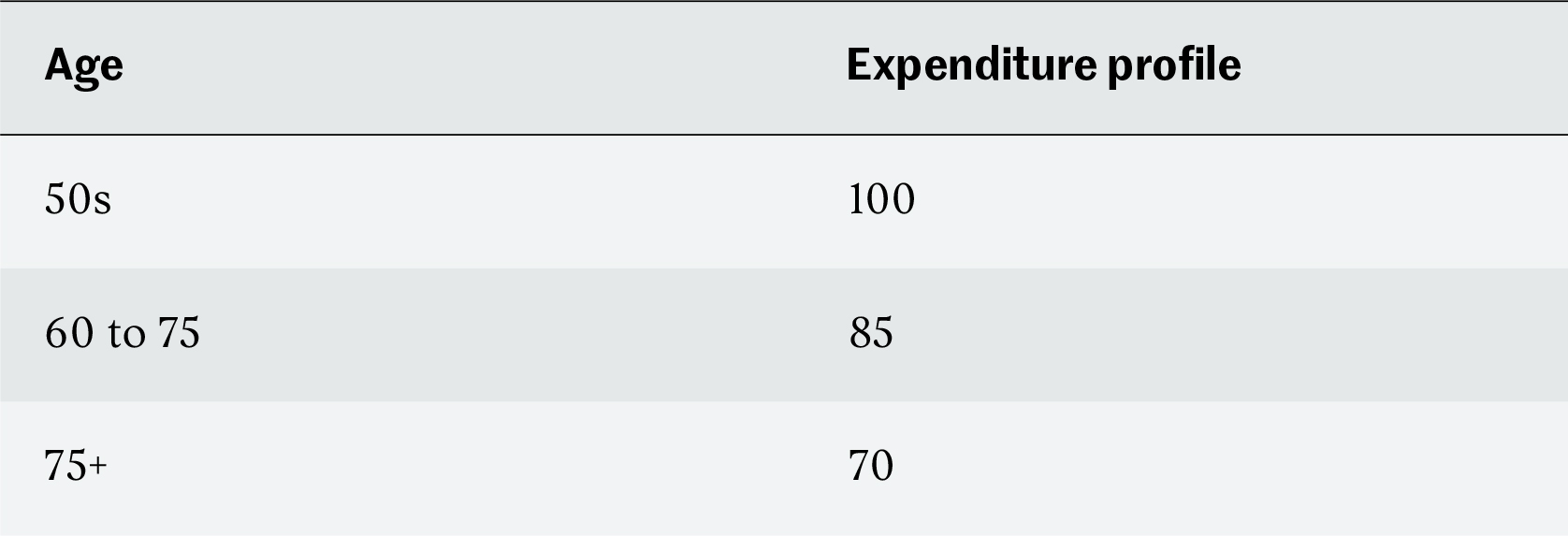

We’re taking account of this in our own expenditure profile as follows. If we think about our core expenditure from 60 to 75 being normalised to 100, we’re assuming a profile through life as follows:

So we’ve set an expenditure level for our initial retirement period, let’s call it 100. In the early years, when we have three children still eager to come on holiday with us, we want to be able to spend a bit more, but from age 60 some of these costs will decline and we think we can live on 15% less.

Beyond 75, we’ll hopefully be going on holiday with our children rather than the other way round, and in any event we’re likely to be buying fewer clothes, maybe travelling a little less (or less far). Based on the data, we think we’ll be fine with 30% less in real terms than in our fifties.

Allowing for expenditure to decrease rather than increase makes a massive difference to how far your money goes.

Buffer

Most successful professionals are fortunate in having a large financial buffer. This buffer allows you to cut back when investment returns are really poor to give your pot time to recover. Rather than anticipating the worst case outcome by building up a gargantuan fund or withdrawing a small annual amount, you react to events as they occur.

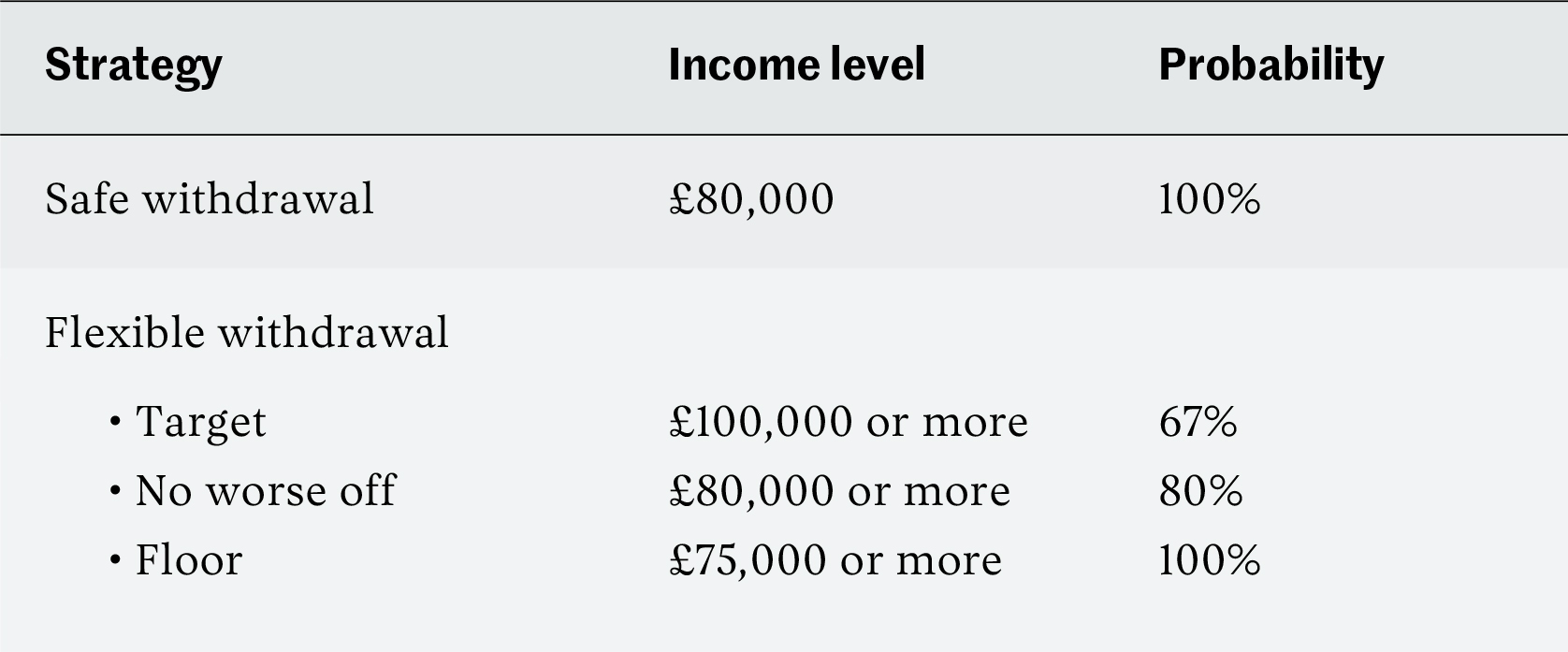

Going through this in detail is a topic for another article. But as an example there’s a flexible withdrawal strategy that enables you to increase your target income by between 20% and 25% with success two-thirds of the time, provided you’re prepared to take some risk. The worst case is an income between 5% and 10% lower than making no change. For example:

If you’re prepared to put up with this level of risk, then you can increase the target amount you take out of your pot at the outset by around a quarter, provided you’re ready to react when you need to. For many people the risk of cutting their expenditure by up to one-quarter is one they can’t take. For successful professionals, this would still likely leave you with much more than most people get by on quite happily.

Back to 4% after all

So let’s work back up, taking this insight into account.

*In these scenarios the withdrawal rate defines the initial income, which then reduces over time

So for successful professionals, maybe the 4% rule isn’t so bad after all, despite the many criticisms. And there’s more in its favour.

You will likely have more income

Few successful professionals, moving to a new phase of life in their fifties, move completely away from earning money. A consulting project here, and board membership there, or a coaching assignment — all these help reduce the strain on your pot in the early years.

At this time of life other, sadder, sources of income may also arise: an inheritance.

All of this counsels against excessive caution when deciding whether you’ve got enough or whether you need to continue on the corporate treadmill for a few more years.

What about care costs?

The spectre of care costs is one that is often cited as the reason for assuming massively increasing expenditure in later life. But data suggests that fewer than one in ten people stay in a care home more than six years. There’s around a 99% chance that you and your spouse need fewer than 12 years of care between you, at a total cost of, say, £1m. By contrast, 75% of people stay in care fewer than three years.

So long term care, while admittedly expensive, has a plausible cost below the value of most successful professionals’ homes. Given the low probability and high uncertainty of the cost, I’ve always viewed our home as the hedge against unexpectedly long care home needs (sorry kids!) rather than trying to save separately for it.

Don’t be too cautious

Approaching retirement is a time when a good financial planner can really earn their fees, in terms of doing the right cashflow modelling, advising you on complex pension issues and the like. But unfortunately the level of competence in retirement income planning is in general quite low, with few having detailed knowledge of the issues I’ve discussed here. Increasingly, retirement income planning is being seen as a specialist topic in its own right.

If you do choose to get financial advice on this topic, be sure first to understand your own parameters:

- How do you see your expenditure needs in retirement? Will you really need the same amount in real terms at 80 as at 60? Develop, and insist that your planner models, your own target expenditure profile. Based on the data, this should decrease in real terms over time.

- What’s your buffer? How much risk of lower expenditure are you prepared to take for a chance of higher income? What’s your non-negotiable baseline? Could you countenance living on 75% of your target or even less?

In general, professionals are a cautious bunch. This caution has a compounding effect. First, we assume we need more income than we really do to live a good life. And second, we assume we need a bigger pot than necessary to secure it. And so we work longer and accumulate more, potentially putting our lives on hold. The only thing this enhances is the amount of money we leave behind when we go.

In this context, despite its weaknesses, the 4% rule remains a surprisingly good benchmark for successful professionals when asking themselves the question: have I got enough?

Important

Nothing in this article should be taken to represent financial advice. It is generic commentary based on typical circumstances and not tailored to your own situation. If you’re not sure what to do, you should take financial advice.