INVESTMENT

How do Nobel laureates approach retirement?

Rules of thumb adopted by the financial advice industry are found wanting by two titans of financial economics.

William F. Sharpe, Nobel laureate of Sharpe ratio fame, has called drawing down income in retirement ‘the nastiest, hardest problem in finance’. Why so? The combination of two sources of major uncertainty: mortality risk and investment risk. And these risks are wreaking their havoc while at the same time you are gradually depleting your pot by drawing income.

In the last decades of the 20th century a typical successful professional would’ve had a generous final salary pension guaranteeing between half and two thirds of their final salary for life. Having a level of guaranteed income that so fully meets likely retirement needs certainly simplifies life. Today, most retirees rely almost entirely on a portfolio of assets to see them through until they shuffle off this mortal coil.

According to Sharpe, and his fellow Nobel laureate Robert C. Merton, the way the financial advice industry has responded to this change is less than ideal. Sharpe and co-authors Jason S. Scott and John G. Watson have critiqued financial advisors’ ‘rules of thumb’ which are ‘inconsistent with expected utility maximisation’ (translation: making the best use of your money). Merton has written of a ‘crisis in retirement planning’ following the shift from defined benefit to defined contribution pensions.

The inherent conflict between risk and certainty

At the heart of both men’s criticisms is the concern that the industry is glossing over the inherent conflict in trying to use a risky investment portfolio to provide a certain income.

Most retirement planning approaches start with an expenditure plan and then develop an investment approach that seeks to meet it. The simplest example of this is the so-called ‘4% rule’. Under this rule, retirees are told that they can take 4% of their initial pot as a retirement income, increase it by inflation each year, and be confident that their pot will last 30 years, if it’s invested in a 60/40 mix of stocks and bonds. But while the 4% rule might be a decent rule of thumb for answering the question ‘Have I got enough?’, it’s not a good basis for managing retirement withdrawals. The reason: the complete mismatch between a fixed inflation-linked withdrawal and a risky investment portfolio of stocks and bonds.

Let’s look at some figures. On my US dataset and ignoring adviser fees, then 94% of the time, the 4% rule would have worked for at least 30 years before the fund ran out. In fact, on each of these 94% of occasions the fund would have sustained this level of withdrawals for over 50 years! The median fund after 30 years was 30% higher in real terms than the initial fund at retirement. By contrast, the worst case had the fund running out after 26 years.

This mismatch between risky investment strategy and fixed withdrawals means walking on a tightrope. On one side you fall off without having money to last you. But in the vast majority of cases, you spend far too little and end up with a fund bigger than you started! Sharpe highlights this mismatch as a major source of economic inefficiency.

Matching investment and expenditure

What’s the solution? The investment strategy and the expenditure plan need to be viewed as an integrated whole. In other words, the risk you take with your investments should match the risk you can take with your expenditure.

Most risk appetite questionnaires focus on figuring out how much short term investment volatility a client can withstand. But in retirement what matters is not investment volatility but your ability to meet your expenditure goals. As Merton states:

“Investment decisions are now focused on the value of the funds, the returns on investment they deliver and how volatile those returns are. Yet the primary concern of the saver remains what it always has been. Will I have sufficient income in retirement to live comfortably? Clearly, the risk and return variables that now drive investment decisions are not being measured in units that correspond to savers’ retirement goals and their likelihood of meeting them. Thus, it cannot be said that savers’ funds are being well managed.”

This leads us to the concept of matching. Both Sharpe and Merton favour thinking about matching each year’s future expenditure with an appropriate asset that creates the right profile of return.

Suppose I know that I want to be able to spend £50,000 in 2050, increased by whatever inflation is between now and then. The closest match to that expenditure is to buy an inflation-linked government bond that matures in 2050. Once I’ve bought that bond, I’ve perfectly matched the expenditure. Even though long-dated government bonds are very volatile (they tend to be very sensitive to even small changes in interest rates) this doesn’t matter. Any subsequent changes in the value of the bond are irrelevant: the bond perfectly meets my expenditure goal. Merton shows that assets that are quite volatile may be a perfect match for a retirement income that is fixed in real terms. Whereas apparently stable assets may in fact be dangerous.

This doesn’t mean that you have to buy a bond to match the expenditure. But if you don’t, then you’re taking a risk that the expenditure cannot be met. If I could live with the expenditure dropping to £25,000 in real terms then maybe I cover half of it with a government bond and invest the rest in riskier assets. This gives me the hope of higher upside, but with the possibility that I won’t do so well.

There’s no free lunch

One of the arguments against this approach is the expense of government bonds. With real interest rates currently negative, the cost of securing my £50,000 expenditure in 2050, increased in real terms, would be around £90,000 today. A globally diversified portfolio of equities has never delivered cumulative negative real returns over a period of longer than 21 years, let alone 29. Surely I’d be better off investing the money in the stock market?

Maybe. But first bear in mind that even the period back to 1900 only provides four completely independent (i.e. non-overlapping) 30-year periods of stock market returns. So not a big sample. Second, not all things that could happen have happened. Insurance is designed to protect us against unknown futures not just realised pasts. Maybe we’ve got a different or more accurate view of the risks than the market. But we should be humble in the face of relative prices formed by millions of informed market participants.

Both Sharpe and Merton believe in informativeness of market prices. There’s generally no such thing as a free lunch.

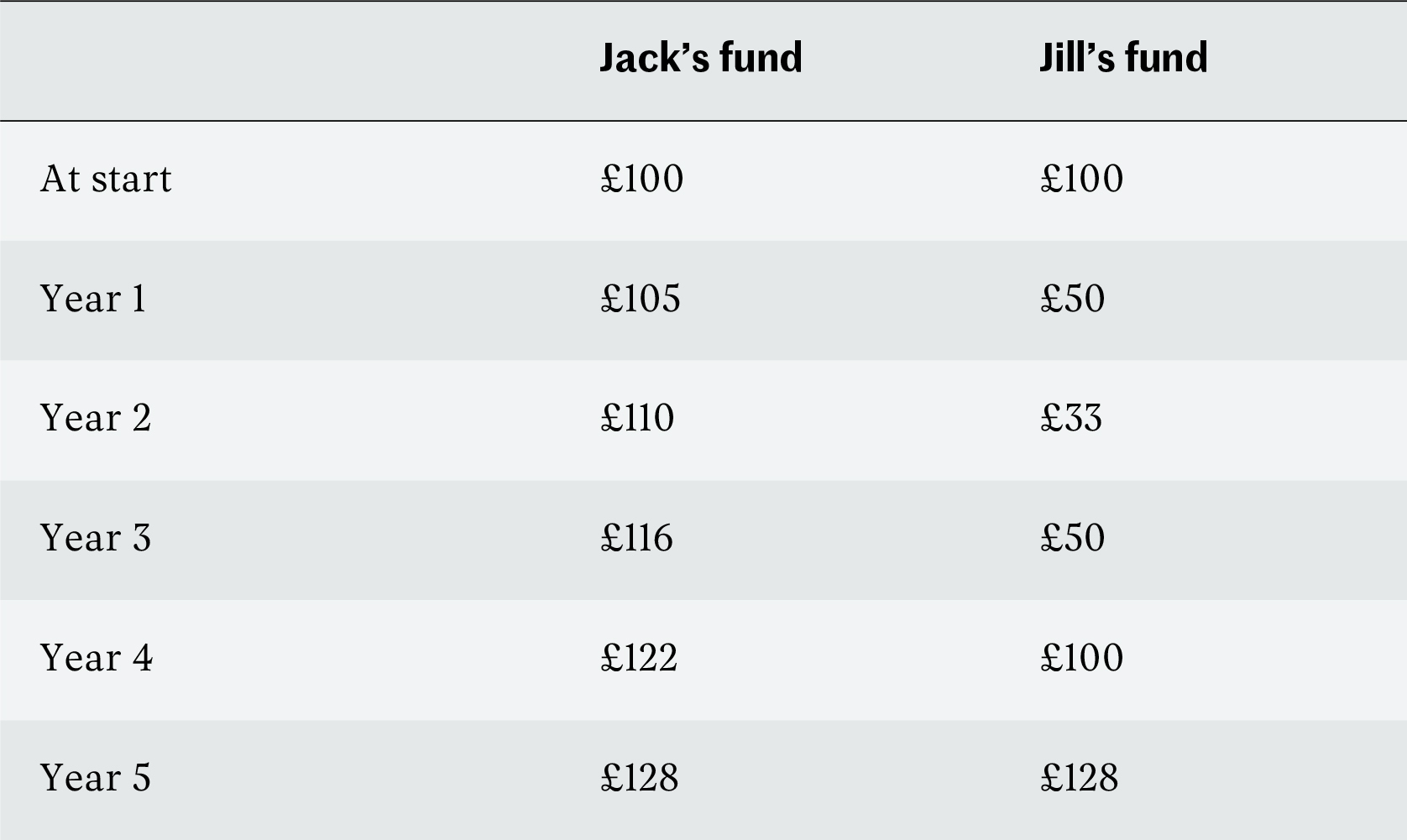

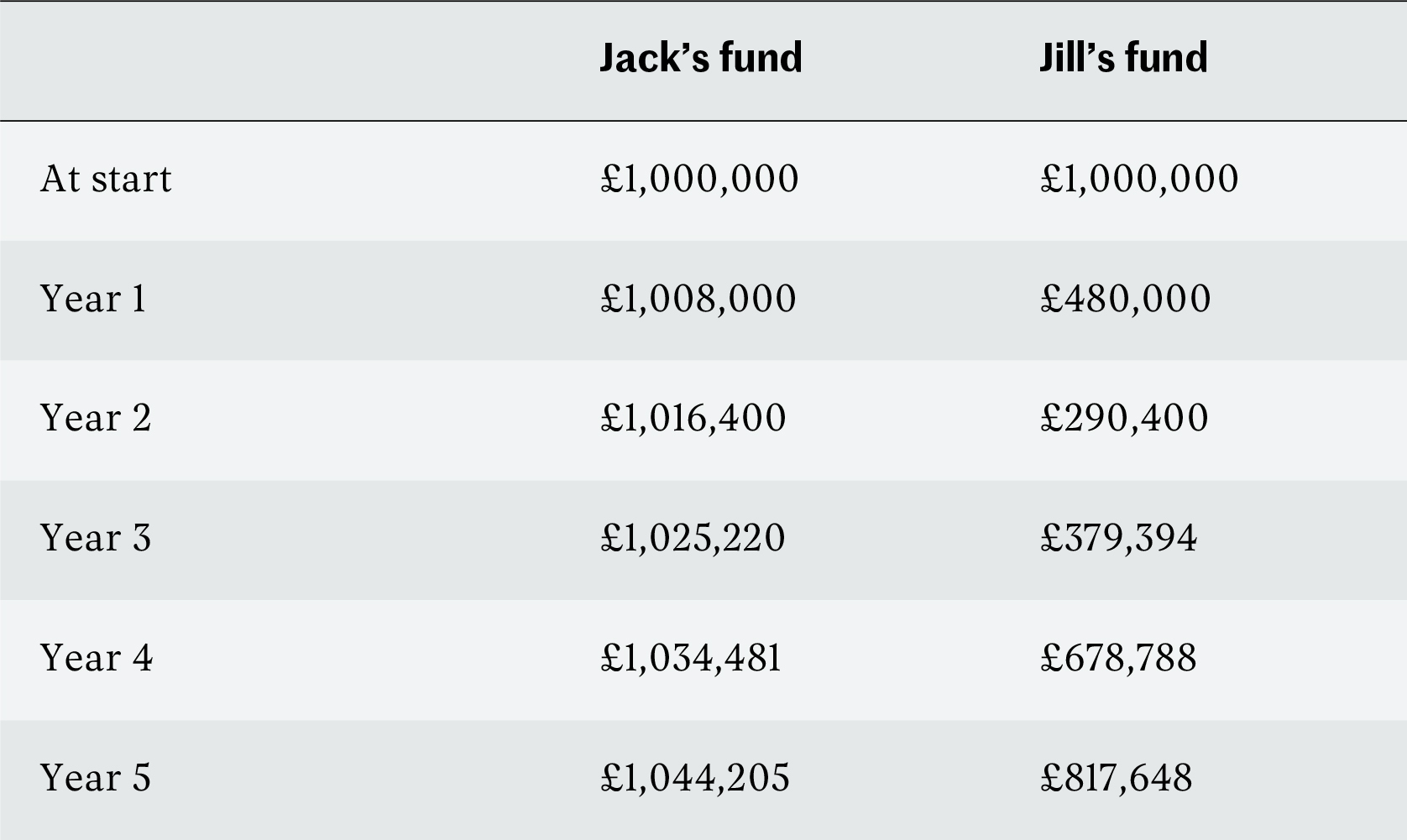

Sequence of returns risk is a self-inflicted wound

The third insight from our Nobel laureates relates to the rather technical ‘sequence of returns risk’. If I am taking fixed withdrawals from a portfolio, then the order in which I get my returns really matters. Let’s take an example. Suppose that Jack and Jill each have a portfolio of £1m and start off withdrawing £40,000 a year from it. Jack’s fund returns 5% pa every year. Jill’s fund halves in year one, falls a further third in year two, then reverses those losses over the next two years, finally increasing by 28% in year five. Here’s how £100 invested in each fund performs over five years.

Both funds deliver the same return over five years. But the impact on the fund values are very different if each withdraws £40,000 a year:

Jack’s fund is still as big as it was in the beginning. But Jill’s is 20% lower. The problem is that because Jill had poor returns early in retirement, each withdrawal ate up a larger proportion of her fund. She’s now spent that money and so cannot recover the losses that she made. The strong returns she made on her fund later on can’t make up for the early losses.

This is commonly referred to as ‘sequence of returns risk’: the risk that poor returns early in retirement, combined with fixed withdrawals, ravage your portfolio with permanent negative impact on your retirement income.

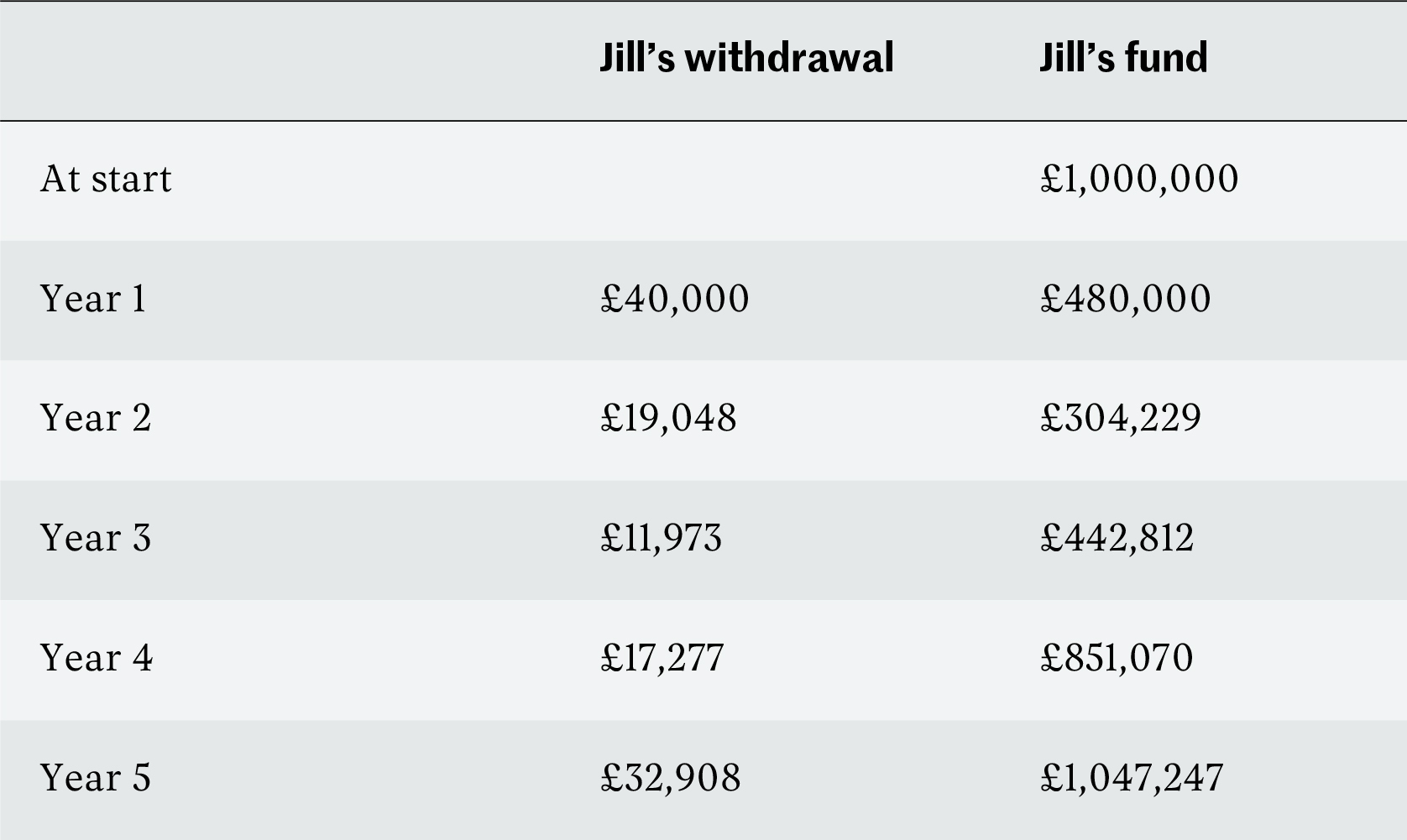

But what if Jill had adopted a different approach, and adjusted each year’s withdrawal in line with the investment return?

Now Jill’s fund is the same as Jack’s after five years, but she’s had to cut her withdrawals heavily in years two to four.

What these numbers demonstrate is that it’s not the sequence of returns that’s the problem. It’s the mismatch between the withdrawal strategy and the investment strategy that gets Jill in hot water. In fact, Sharpe and his co-authors show that the so-called sequence of returns risk is a mismatching risk that doesn’t get rewarded by higher returns, and so is economically inefficient for the individual.

The reductions in income faced by Jill in the early years look uncomfortable. But this then suggests her investment strategy is too risky. The fixed withdrawal approach masks that fact, for a while, but has a nasty sting in the tail when she runs out of money early.

So what do our Nobel laureates propose?

Sharpe’s solution is the so-called ‘lock-box’ or ‘earmarking’ strategy:

- Pick a year in the future, let’s say 2040.

- Determine your minimum required expenditure and your desired expenditure in real terms for 2040.

- Estimate the risk-free investment (e.g. an index-linked government bond) required to cover the minimum required expenditure.

- Estimate the risky investments (e.g. stocks) required to fund the excess to get to your desired expenditure.

- Earmark those investments for 2040 and don’t touch them until 2040: put them in a 2040 ‘lock-box’.

- Repeat for all other years.

Each lock-box has its own investment strategy in terms of asset mix, whether or not you rebalance investments and so on. It separates out the risk-reward trade-off by each year and so avoids sequence of returns risk. It ensures that you spend enough as well as not spending too much. The problem: it’s a bit complicated with potentially 50 different pots of money to manage!

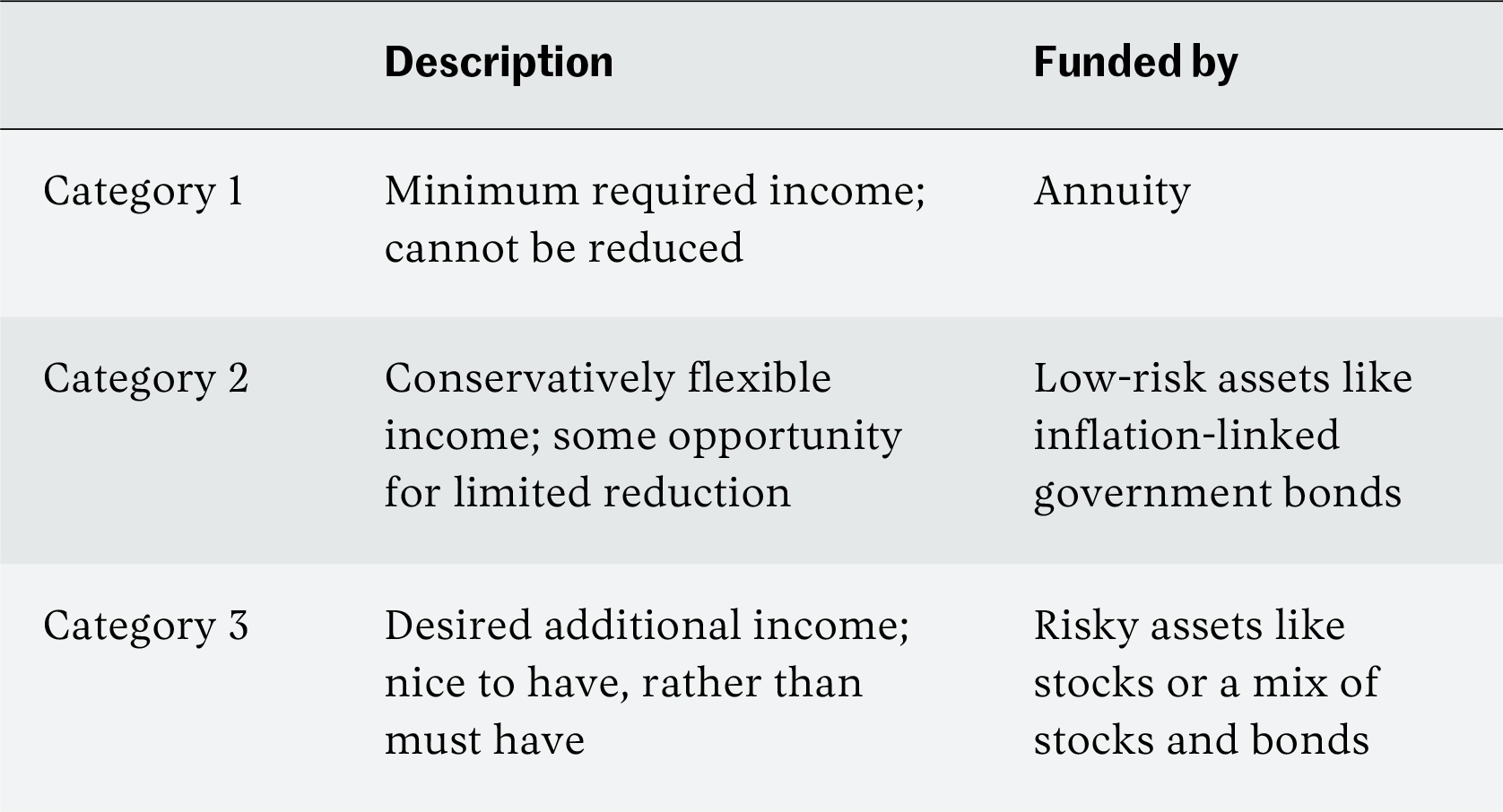

Merton’s solution isn’t so different, but is simpler in practice. He recommends identifying three categories of income:

Common to both our Nobel laureates is the idea that we need to choose the investments to match our expenditure needs and according to the risk we’re prepared to take. Short term fund volatility is irrelevant. Of course, we may find that there’s a gap between what we’d like and what we can achieve. We may have to take more risk than we’d like to give ourselves a chance of the income we want. But we should do that in full knowledge of the possible consequences.

Insights for successful professionals

What should successful professionals take from the Nobel prizewinners as they approach drawing down on their painstakingly accumulated assets? I draw the following lessons.

Think about securing a base level of income

Most successful professionals have a target level of expenditure that is some way above what they could survive on comfortably. Reflect on the minimum level of expenditure you need for a dignified retirement and think about securing it. In my view, annuities are an undervalued retirement planning tool. You may not want to buy an annuity immediately. But you should think about buying now a portfolio of index-linked gilts (or, second best, a long-dated index-linked gilt fund) to ensure that you’ve matched the cost of buying an annuity at some time in future.

There’s no free lunch

Higher returns come from taking more risk. There’s no such thing as a free lunch from investing in equities rather than buying an annuity or investing in bonds. The risk may be small, but low probability risks are often high impact.

Are annuities expensive because the market has gone nuts? Or is it because low prospective returns, high volatility on risky assets, and uncertainty about trends in life expectancy make the insurance they provide particularly valuable? We don’t know for sure, but I’m not prepared to bet on market insanity.

Have a flexible spending plan

The way to avoid both running out of money and ending up with too much is to have a flexible spending plan. Successful professionals are used to having around half their pay as salary and half in the form of bonuses or long-term incentives. You can think about retirement in the same way. If you’ve secured a base using a mixture of annuities and low risk assets, then you can set up a withdrawal plan for the rest of your pot that fluctuates with investment returns. This takes so-called “sequence of returns risk” off the table. You can manage the trade-off between level and volatility of expenditure through your asset mix. And you can be confident both that you will neither run out of money nor die too rich.

Financial economics provides valuable insights into how we should manage our personal investments. The world may not fully reflect the idealised circumstances assumed by these Nobel laureates. But their work provides genuine insight that we, and the industry, ignore at our cost.

Important

Nothing in this article should be taken to represent financial advice. It is generic commentary based on typical circumstances and not tailored to your own situation. If you’re not sure what to do, you should take financial advice.