INVESTMENT

How I invest

A successful investment strategy is one that gives you a good shot at meeting your goals while allowing you to sleep at night.

I’m doing a short series of articles on investment. This is a vast topic and I don’t want to write a textbook. After a number of false starts at bringing all the themes together, I’ve decided that the easiest way to bring the issues to life is to explain the investment approach I use for my pension and other assets, and to discuss the issues that flow from that, and how I address them. This won’t be comprehensive and of course what’s right for me may not be right for you.

But anyway, here goes.

Know thyself

There’s no point having a plan if you can’t stick to it. So knowing your likely psychological trigger points is important. The typical risk-attitude questionnaire that an adviser will get you to fill out assumes that we all sit on a spectrum of risk attitude from risk averse to risk seeking (you can try free ones here or here). The key risk parameter considered is the short-term volatility we’re prepared to stomach in our investments. Somehow this attitude to risk is assessed independent of ability to take risk, as measured by your future earning power and the gap between your resources and your needs. Moreover, the risk rating then leads to a recommended portfolio mix without any regard to the flexibility of your financial goals in terms of timing or amount. This just doesn’t make sense to me. As personal finance expert Paul Claireaux is fond of saying: attitude to risk is not the same as capacity for risk, and if anything the latter is the most important.

My own risk attitude score is pretty middle of the road. Slightly more risk-tolerant than average. But that average hides a lot of nuance. I’m actually quite risk-averse about tail risks: the small probability that something goes horribly wrong. The possibility of running out of money in later life is something I find it difficult to relax about. So I’ve always had in interest in building a bullet-proof (as far as is possible) minimum income baseline that will last for life. This is some way below my desired income, but is at a level that would be just about enough.

At the same time, I really don’t want to be worried about whether I’m spending too much right now. So I like to have three years of expenditure in very low risk investments so at least I can book my holidays in peace and know I’ve got a couple of years to make any necessary course corrections if markets turn against me.

Once I have certainty in place about a lifetime minimum level of income and my short-term expenditure needs, I feel comfortable about taking much more risk in the rest of my investments. Short-term investment volatility really doesn’t bother me. So, I have greater risk tolerance than average, but only once I’ve covered off the extreme downside in both the short and long term.

The beauty of buckets

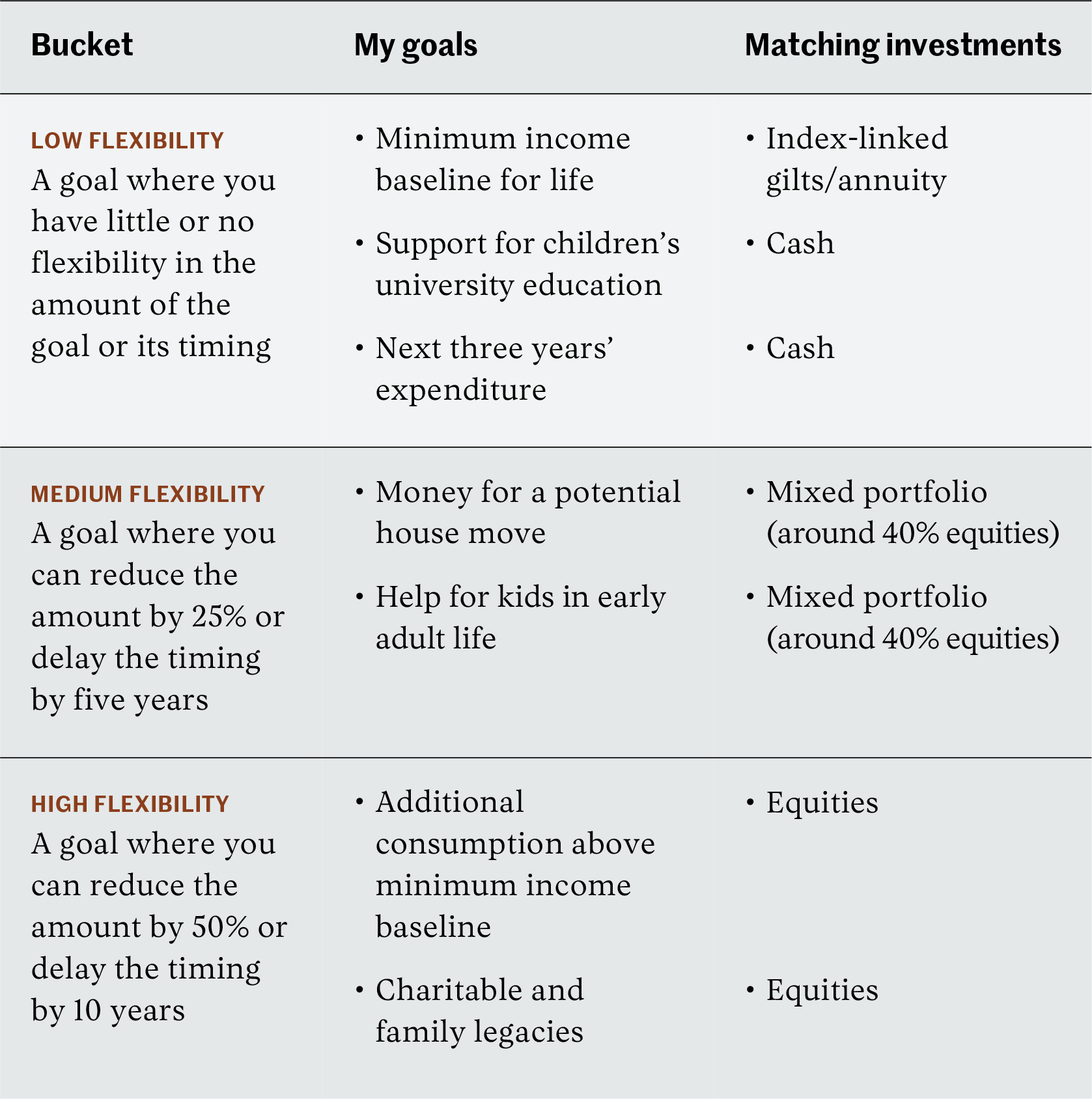

As I’ve written elsewhere, my whole investment approach is based on the idea that a robust investment strategy has to be linked to your financial goals and, crucially, the extent to which they are flexible in timing or amount.

So it helps me to think in buckets. A single portfolio blended to an average risk profile that I use to meet all my objectives doesn’t work for me, although I recognise it may do for some of you. I much prefer dealing in pots of investments that are designed to meet specific goals with appropriate risk. My overall asset allocation is then the result of aggregating these pots. Although this is an example of potentially inefficient mental accounting, I find this compartmentalisation creates a level of assurance in my mind that I’ve got all the bases covered. My work with clients suggests I’m not alone in this preference. And some Nobel laureates agree as well.

Perhaps it’s my actuarial training that causes me to want to match assets to liabilities and to decide on investments according to the level of flexibility in my goals. I think about goals in three broad buckets. The level of flexibility of the goal, in terms of timing or amount, determines which bucket it goes in, and which investment is a suitable match for it. This is how the theory converts to reality in my case:

In aggregate this results, for us, in a portfolio that is roughly 60% equities and 40% in cash and bonds: the classic 60:40 portfolio. But it’s arisen from a bottom-up process of matching investments to goals, rather than a top-down process based on a risk attitude score. And I manage it quite differently from the conventional approach of a single portfolio of equity and bond funds, rebalanced on a quarterly or yearly basis. I’ll come back to some of the nuances of the approach, and why I follow them, in future articles:

- Rather than using an index-linked bond fund for matching my minimum income baseline I use a series of passively held index-linked bonds with maturity dates spread over my future lifetime (a bond ladder). In due course I will sell these bonds to buy an annuity.

- While I rebalance investments within each bucket, I don’t rebalance between buckets, because each bucket has its own investment strategy and associated risk.

- My high flexibility bucket is all equities, invested using low cost systemic or index investment approaches rather than active stock picking.

- My medium flexibility bucket includes some gold and commodities as well as equities and short and long-term government bonds.

What price peace of mind?

With each bucket’s investment strategy set up to match the flexibility, in amount and timing, of each future goal, I have a ‘set and forget’ approach that enables me to endure market volatility with equanimity, knowing I’ve set up the component parts to align with my capacity for risk. As a simple example, my index-linked gilts have fallen about 15% in value over the last few months as interest rates have risen. But because I will hold them until they mature, the long-term inflation-linked stream of income they will provide is entirely unaffected by this short-term price volatility and so the market turbulence is irrelevant. The equity portion has also fallen, but I know I have three years’ expenditure covered by lower risk investments and I can manage the volatility by flexing my expenditure beyond this, given the underpin from my minimum income baseline.

Having removed anxiety about the very long term and provided certainty for the short term, I can let my natural myopia hold sway; I don’t worry too much about what happens over the medium term, leaving markets to do their thing.

And meanwhile, I can enjoy life and sleep well.

Important

Nothing in this article should be taken to represent financial advice. It is generic commentary based on typical circumstances and not tailored to your own situation. If you’re not sure what to do, you should take financial advice.