FAMILY

Providing for children

Planning the financial legacy you want to leave your children comes down to: why? When? And how much?

Why?

It may seem like a stupid question, but it’s important to understand why we’re giving money to our children. Sometimes we just drift into it because it’s expected. It’s what successful professionals do. But we need to dig a bit deeper, and recognise a mix of complex emotions and motivations can also come into play:

- Helping our children live a better life.

- Reducing our own anxiety about our children’s future.

- A recycling of, or reaction to, our own experiences with our parents.

- Expressing our love for our children.

- Make up for guilt about mistakes we feel we’ve made with our children.

- A desire to retain some control over our children.

- Making our children love us.

- Keeping up with what our friends or family are doing for their children.

Some of these we’ll acknowledge. Others lurk in the background. It’s worth unpicking what’s at play, to ensure it’s not distorting our decision making.

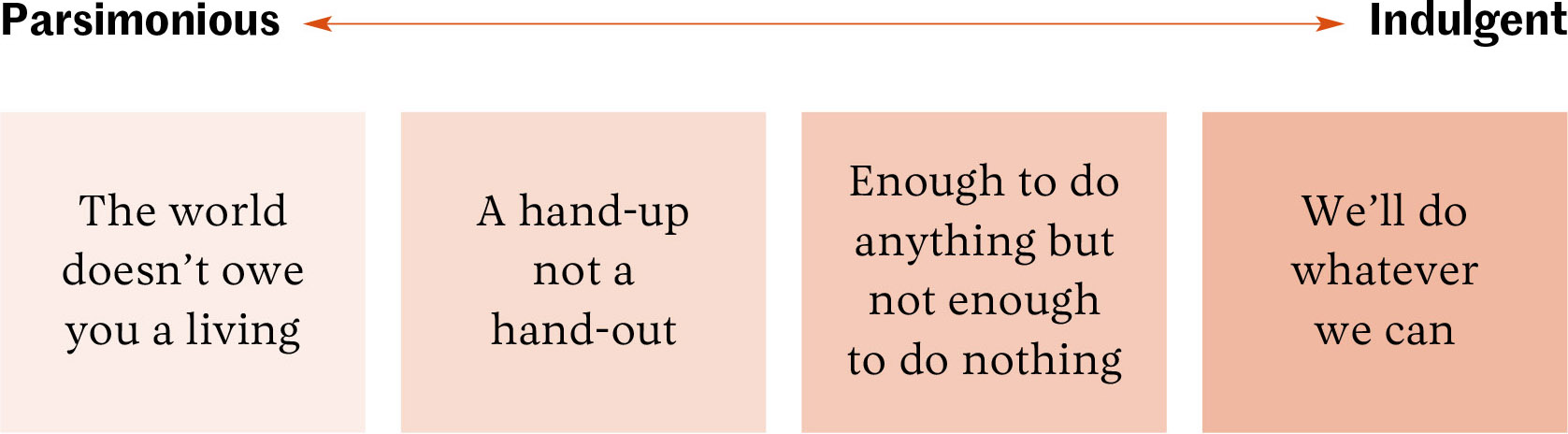

These underlying emotions can trigger money beliefs relating to legacy. I see a range of attitudes amongst clients which I put on a spectrum from parsimonious to indulgent.

At one extreme the indulgent parent does everything they can for their child. Buys them a house and a car, sets up a trust fund sufficient to support them for life, and so on. By contrast the parsimonious parent acts as if the money doesn’t exist. The child is denied even normal support and has to work for everything themselves.

And often we focus too much on the specifics of what we’ll give. But the values we instil in our children through the example we set and the opportunities provide to help them learn for themselves are much more important than the amounts or mechanics of what we give them financially.

As with most things in life, the right answer is rarely at the extremes. Overindulgence can lead to loss of agency, a sense of drift and lack of purpose and a sense of ennui that in many public cases has led to severe mental health problems and self-destructive behaviour. At the other extreme, imposition of excessive false scarcity can feel like punishment and create a fear or anxiety about money that is unwarranted.

How do you find the happy medium?

The starting point is to think through what you want your children to have in their lives and how you can help them get there. Most of us, when asked, will say we want our children to be independent, competent with money and to have a relationship with money that puts it in its proper place, as the servant to a life well lived rather than its master. So here are some questions to ask yourself and discuss with your partner when considering a financial legacy.

- What lessons do I want my child to learn about money?

- How will this legacy build skills and competence in my child that will stand them in good stead?

- How will this legacy help my child be a better person and live a life that contributes to the wider good as well as their own wellbeing?

- What needs do I have that I am seeking to meet through providing this legacy?

- What are the risks of this legacy for my child and our relationship?

This reflection can also help to flush out some of the motivations for giving that are more about us than them.

And it may well lead you to giving your children less than you at first thought. But often the answer won’t be to give them nothing at all. Just looking at help with house purchases, research by Legal & General and Cebr found that more than half of house purchases by first-time buyers under the age of 35 are supported by BOMAD (the bank of mum and dad). Which leads us onto when to give it.

When?

Legacy has typically been associated with wills and death. But increasing life expectancy is changing attitudes on giving to children. Data from the ONS shows there’s a 1 in 10 chance of at least one of a 50-year-old couple living until 100. By which time your children are likely to be well into their retirement. It’s probably going to be much more useful to your children to have a smaller amount of financial help earlier in their lives than a windfall in their retirement.

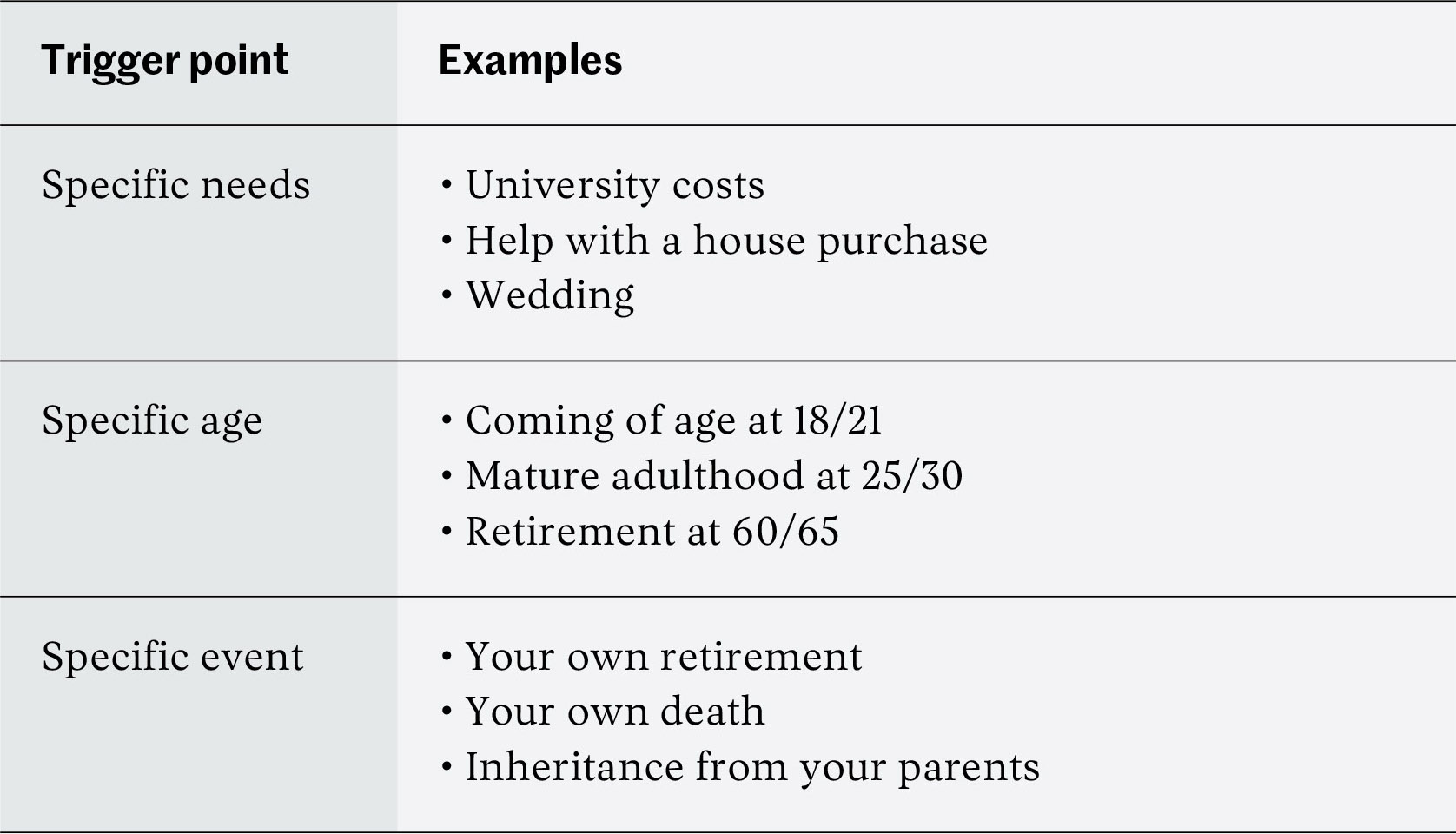

There’s a range of potential trigger points.

Of course, these triggers can be linked. You might save into a junior ISA, which passes to your child at age 18, while making it clear to them that this includes the support you would give towards a house purchase.

You may feel more comfortable agreeing to provide support for specific events, such as a wedding. Alternatively, you may prefer to provide a set amount of support at a specific age and leave it up to your child how to use it. Finally, the timing may be triggered by events in your own life, such as taking the tax-free cash from your pension.

These are very personal choices, but I think there’s something to be said for making the gifts as unconditional as possible. This gives your children responsibility for their decisions, encourages them to make their own trade-offs and guards against you trying to micromanage their decisions.

How much?

This is a very personal choice. I’ve seen people for whom the ‘right’ level of support is a £20,000 deposit on a starter flat and others for whom it’s the £200,000 starter flat in its entirety or more.

Given the challenges young people face today it can be tempting to build up a war chest to protect them against any eventuality. But will that really help them to be happy? Would you have wanted that for yourself? Go back to what you’re really trying to achieve. I do think there’s something to be said for the philosophies of ‘hand-up not hand-out’ or ‘enough to do anything but not enough to do nothing’. I know this is tough. I’ve oscillated myself between a desire to do all I can to protect my children financially from the world’s uncertainty and a desire to avoid spoiling them, to give them agency, and to equip them to deal with the world.

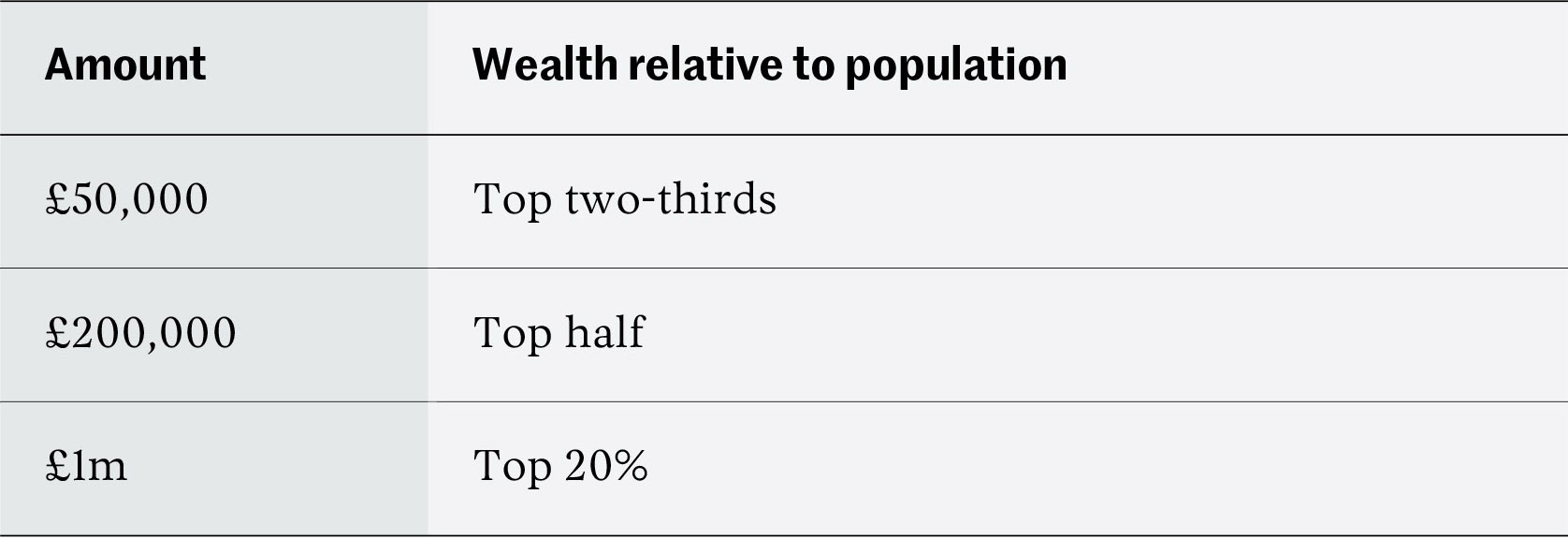

It’s important to keep things in perspective. The research by Legal & General and Cebr found that only 1 in 5 first-time buyers received a contribution of more than £30,000 from BOMAD. A fund of £50,000 can reasonably cover a flat deposit and a wedding with something left over. Or can fund a year’s retraining or qualification. And this amount would immediately propel your child into the top two-thirds of the population in terms of net wealth (see the table). At the other extreme, a fund of £1m looks dangerously like making work optional and immediately puts your child in the top quintile of net wealth.

On this table, ‘wealth’ means the total of financial, pension and property net wealth (source ONS).

Anything that you do for your children will be more than most children get. It’s also important not to imperil your own happiness and future in order to meet an excessive financial goal for your children. It sets a bad example, they probably won’t appreciate it anyway and it stops you living your own life. A misplaced sense of obligation is no good for anyone.

Talk about it

Being clear on why, when and how much you want to give your children helps free you to live your own life. A vague sense of ‘I should do more’ is corrosive and encourages delay in living the life you want to lead. It’s important for partners to communicate on this. I’ve seen couples not realising they had radically different ideas about what constitutes an appropriate level of financial support for their children. And it’s important to speak to your children too, so they know what to expect, and what’s expected of them. According to the Money Advice Service fewer than 1 in 10 parents have talked to their children about their inheritance.

When it comes to your financial legacy, it’s important to ask why? When? And how much? When it comes to the money, less may be more. Most important is the financial legacy you leave your children in terms of the values you instil and the example you set.

And above all else, talk about it.