INVESTMENT

Investing for good

There’s no clear consensus on how individual citizens should best use their investments to save the planet. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try.

A longer version of this blog, with references to supporting academic evidence, can be found in my climate change blog series.

How should we invest to support progress towards addressing climate change?

Friends of the Earth are clear: we should divest from companies involved in extraction of fossil fuels.

Others disagree. Speaking to the Financial Times in 2019, Bill Gates said, “Divestment, to date, has probably reduced about zero tonnes of emissions.” Instead, we should be investing in the breakthrough technologies that we need to bend the curve of emissions: artificial meat substitutes, low carbon cement production, and so on.

At the furthest end of the spectrum, Merryn Somerset Webb of the Financial Times asserts that we should buy more oil stocks: we still need oil, and it’s better that as many oil stocks as possible are in the hands of responsible owners who will engage with them to transition faster to a low-carbon world. If we divest then these companies will be owned by unscrupulous investors who care much less about climate change than we do.

Pretty bewildering, huh?

In this article I’m going to try to provide a simple (and I hope not too simplistic) guide. I’m going to focus on climate change, but the principles could apply to other environmental or social issues. In almost all cases, you can replace ‘climate change’ with your favourite concern.

I’m going to focus on how investors can best help bring about change on climate issues through their investment decisions. I’m setting aside for now the question of whether this has a cost in terms of returns (as you’ll see we’ve enough to cover as it is). I’ll come back to the trade-off question in a separate article.

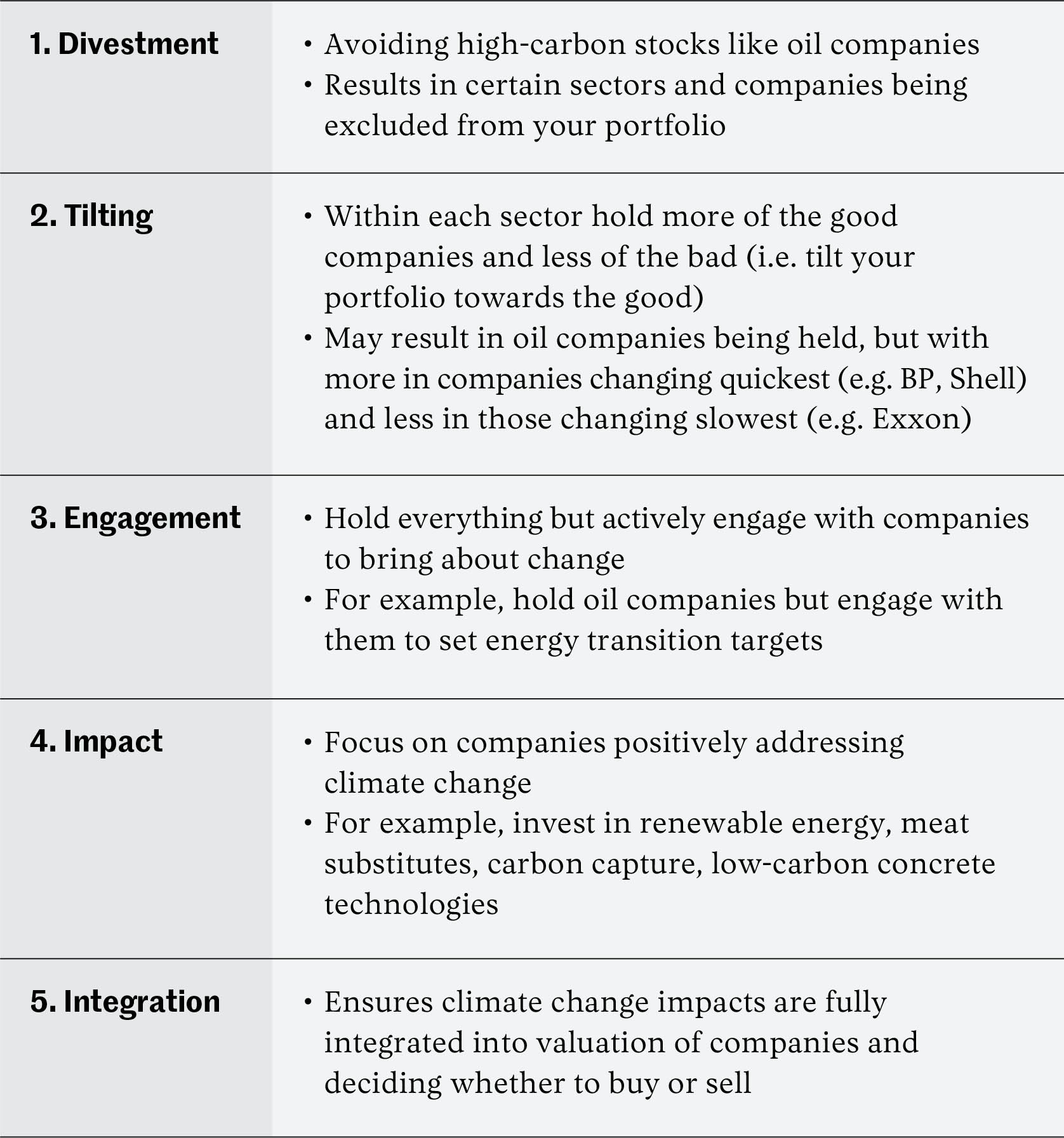

Five roads to virtue

1. Divestment

The economic logic of divestment is as follows: if sufficient numbers of investors choose not to invest in the shares of oil & gas and coal companies, then their cost of equity will rise. This will raise the threshold rate of return on investments, therefore reducing investment in those industries. In extremis, these companies could be starved of capital altogether.

Although divestment seems a simple approach to the problem, there are multiple problems with it as an approach.

- First is that few people are prepared to do without the proceeds of the oil and gas industry. If we still need oil and gas companies for the foreseeable future, isn’t it hypocritical to wash our hands of investing in them?

- Second, if we don’t invest in them as listed companies they may simply be taken private by less scrupulous owners who care even less about the climate and will be free to act as they wish out of the public eye.

- Third, stopping listed oil and gas companies from extracting reserves doesn’t solve the problem. It’s estimated that listed companies own a little over a quarter of fossil fuel reserves. Even if divestment completely stopped extraction of listed company reserves (which is unlikely) then we’d still have in private and state-owned company hands around three times the reserves needed to fry the planet.

- Fourth, it doesn’t seem to work. There’s no concrete evidence of divestment campaigns being successful in raising cost of equity for affected firms or reducing access to capital. Indeed, evidence currently is that unsustainable firms don’t seem to face greater problems than sustainable ones in raising financing. Of course, this could change if more people adopted divestment strategies. But that would require a mass change in behaviour that isn’t immediately on the horizon.

- Fifth, even if divestment hits share prices, it doesn’t affect incentives. This is because an oil and gas company can’t overnight decide not to be an oil and gas company. Therefore, the executives just have to accept any share price hit and move on. There’s no action they can realistically take to avoid divestment.

The main benefit of divestment in equity portfolios is therefore the communication and signalling impact. This shouldn’t be discounted. But perhaps it can be combined with approaches that are economically more effective.

Divesting from fossil fuel companies in their equity portfolios doesn’t seem to be a very effective way for retail investors to exert economic influence on climate change. Any impact will be through the political signalling of such an action.

2. Tilting

The logic behind tilting is subtly different to divestment. Rather than trying to starve an industry of capital, tilting aims to create incentives for companies to change direction.

There are many variations of this approach, so I’ll use a simple example in which a fund invests in different sectors according to their market capitalisation weights. So let’s suppose that energy forms a 4% weight in a global equity market index. Let’s further suppose that within that 4%, Exxon accounts for 5% and BP accounts for 2% by market capitalisation.

The tilted fund maintains the sector weighting, so 4% is invested in energy. However, it assesses the sustainability pathway of each company within the energy sector. As a result of this suppose it applies a weight of 0.5x to Exxon, which is on a slow transition pathway, and a weight of 2x to BP, which is on a rapid transition pathway. As a result, within the energy portion of the fund, 0.5 x 5% = 2.5% is invested in Exxon and 2 x 2% = 4% is invested in BP. Despite BP being less then half the size of Exxon, the fund ends up holding nearly twice as much in the greener company.

Why does tilting help? By selling down Exxon and buying BP, the fund contributes to downwards price pressure on Exxon and upwards pressure on BP. This hits Exxon executives and rewards BP executives through their shareholdings. Why is this any different from divestment? The crucial difference is that tilting creates an incentive for Exxon to become more like BP. Whereas with divestment there is no strategy that Exxon directors can follow that will affect the outcome (they can’t realistically stop being an oil company) with tilting there is: they can adopt a more aggressive transition pathway.

Overall, the evidence in favour of tilting is much stronger than divestment, particularly when it comes to holdings of equities. Another big advantage of tilting compared to divestment is that it can be applied across all sectors. Every sector has better or worse companies from a climate perspective but you can’t divest from everything. A tilting strategy can go after them all, unlike divestment, which will typically only address the energy sector or problematic sectors like controversial weapons.

Tilting as an approach to climate-friendly investing is an effective approach, which can be extended across all sectors.

3. Engagement

Engagement involves holding shares in companies and using your influence as a shareholder to drive change in the company. A recent example: shareholders in HSBC, co-ordinated by ShareAction, pushed the bank to adopt much more aggressive climate targets including a phase-out of funding of coal projects.

Engagement is a potentially powerful channel. It doesn’t always require a majority of shareholders to act as a catalyst for a company to change. And as the HSBC example shows, shareholders can have a significant impact on banks’ approach to debt financing of carbon-based fuels, thereby having a multiplying effect by engaging with just one company – a reason why investors focussed on this target. Other prominent cases of investor engagement, as with Shell, BP, and Barclays suggest that this is not a one-off.

Evidence suggests that engagement is effective. The effectiveness of relatively aggressive hedge fund activism in delivering change has been documented for some time. But there is also some evidence that lower profile engagement on ESG matters can have an impact. One study found a success rate of 18% for ESG engagements and these were also associated with positive share price returns. Another study of the stewardship processes of a large UK asset manager found that the interaction of engagement and exit strategies proved a powerful governance mechanism.

Overall the evidence in favour of engagement is cautiously positive. And if we return to the case of oil majors. surely it is better to encourage them to become engines of change in the industry, rather than leaving them to be owned and run by investors much less interested in climate change.

How can you tell if your fund manager is engaging on climate issues? Most fund managers operating in the UK are signatories of the Stewardship Code, which requires them to give extensive disclosures on their policies, their approach to sustainability, and how they engage with companies. Just search for [Name of Your Asset Manager] Stewardship Report.

In relation to climate change specfically, you can see if the asset manager is signed up to Climate Action 100+, the Net Zero Asset Manager’s Initiative, or The Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change. Or you can try to find out how they voted on signature resolutions like the HSBC resolution sponsored by Share Action. It takes a bit of digging as it is possible for an asset manager to sign up to one or more of these initiatives without really doing much, so you need to triangulate a number of sources. It can also be confusing because in some cases a fund manager will have a particular sustainable fund that will adopt a more assertive engagement approach than their other funds.

But the evidence is that robust engagement produces results, and that by investing money with an asset manager that is actively engaging, you will be making a difference.

Engagement produces results. It is an important component in the armoury of any climate-conscious investor.

4. Impact

Rather than divesting, which seeks to avoid the problem, investors may choose to try to fund the solution. This is the basis of impact investing. By making capital available for the technologies needed to solve the climate crisis, the idea is to use your investments to help make the world a better place. This might include investing in clean energy funds, or funds that aim to invest in a basket of companies with products that help address environmental problems or other sustainable development goals. In this section I’m going to focus on the example of clean energy.

The economic rationale for the impact approach is that investing in industries that help solve climate change increases capacity for investment, and lowers cost of equity for companies in those industries. This accelerates development of solutions to the climate crisis.

If we look at the renewable energy sector, there has been a huge inflow of money into renewable energy funds that is driving valuations skywards. A recent article in the Financial Times shows the extent of the issue: the S&P Global Clean Energy index now showing a PE ratio double that of the S&P 500 having been broadly comparable at the start of the pandemic.

Anecdotally, it does seem that the flow of funds is leading to new vehicles being set up to intermediate between the desires of investors to be involved in the sector and the opportunities that are available. The presence of more public market alternatives, whether SPACs or direct IPOs, may also create the benefit of providing more exit opportunities for private equity and venture capital, which, in renewable energy, is currently dominated by trade-sales rather than IPOs. This may in turn attract more venture and private equity capital into riskier early stage ventures, which are so vital for breakthrough technology development.

But are these flows sustainably lowering cost of capital in the sector? The systematic evidence is very mixed. If cost of capital is not being sustainably lowered, then impact investment may not lead to a long term increase in investment. There’s a risk that the recent explosion of valuations in the listed renewable energy sector has bubble characteristics, driven simply by the wall of money flowing into funds, and investors chasing what they see as the possibility for higher returns. If sophisticated actors elsewhere in the chain don’t view this as sustainable, then it may not affect real investing behaviour. The reality is that issues like volatility in energy prices and lack of clarity of long-term government policies may be more critical for investment in clean technologies than the availability of capital.

Overall, the case for impact investment (at the level of public equity markets) as a lever for driving change appears to me to be rather weak. Throwing money at the problem at the level of equity markets is arguably like pushing on a piece of string — the changes instead need to come in the fundamental incentives for companies to invest, which will be set by government regulation and consumer behaviour.

Directing our money towards narrowly focused impact funds is likely to contribute to increased valuations for companies that benefit from those funds. Whether this leads to greater investment remains a difficult question to answer and currently the case is not made.

5. Integration

Integration means fully taking climate risks and opportunities into account when deciding how to value a company, and whether to buy or sell its shares. Integration funds typically look at a range of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors, not just climate.

If this just sounds like common sense, remember that some investment strategies don’t take environmental considerations into account at all when buying or selling stocks. Index strategies just buy stocks according to market capitalisation weights. Quantitative strategies like momentum may look purely at share price dynamics and ignore environmental factors altogether.

Encouraging more Integration is a good thing. It means that more investors will take advantage of, and reinforce, the natural long term alignment between shareholder value and ESG factors, as described so powerfully by Alex Edmans in his book Grow the Pie: How Great Companies Deliver both Purpose and Profit. This should result in more capital being deployed to support companies that produce benefits for both shareholders and society.

However, investors need to be aware that with an Integration strategy, everything has its price. Even the dirtiest oil or coal company can one day be cheap enough for the prospective returns to be worth it, even with all climate-related risks accounted for. Integration just means that the risks of stranded assets, future regulation and so on, have to be fully priced in. This of itself is useful as it ensures that issues like stranded assets in oil companies will be fully reflected in valuations and ensures market efficiency. If companies on a rapid transition pathway are indeed taking the most financially sustainable approach, we want this to be reflected in price signals. But it may not help investors who want to drive climate change action quicker than pure financial market forces dictate, even if that comes at a cost.

In practice, ESG Integration strategies may be combined with one of the other strategies referred to above, such as engagement, tilting, impact, or screening out certain sectors. Integration strategies often invest with a theme in mind, but with an aim of using this to maximise returns. While any of the previous four strategies can be adopted by index or active fund managers, integration only makes sense in an active context, as only active managers have choices over which companies to buy or sell.

Investing in funds that follow ESG integration increases the efficiency with which ESG factors will be priced into the market. This will encourage firms to follow ESG strategies where they lead to long term shareholder value. However, this strategy does not enable investors to drive change faster than market forces dictate, unless combined with another strategy.

So where does this leave us?

Having spent a long time looking at all of these issues and reading the academic evidence, I frequently go through periods of feeling that I’m none the wiser for the effort.

But bringing this all together suggests two broad categories of strategy that are likely to be most effective for the climate-conscious, ordinary retail investor seeking to use their money to bring about change.

Preferred strategies for ordinary retail investors looking to accelerate climate action

1. An index strategy with an investment manager that is strongly committed to robust engagement on climate issues, combined with a tilting strategy within the index.

2. An active strategy with an investment manager that is strongly committed to ESG integration combined with robust engagement on climate issues.

Ultimately, there’s not a single clear answer. As my friend and leading sustainable investor Ben Yeoh of RBC says, “There’s not one right answer, but what’s important is to pick one and then talk about why you’re doing it.” Ben’s important insight is that we’re trying to create a movement for change. Any plausible action can support the case for that change and influence the political and social context in the right direction, keeping climate high up the agenda – provided we’re public about it. So consider the issues, make your choice, and be proud! Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.

Because none of this is terribly clear cut, we should also be modest about what our personal investment choices can achieve on climate change. The incentives for capital to flow to the economically most attractive opportunities are very strong. Affecting climate change through investment choices is a bit like pushing on a piece of string. More important will be getting governments to set the right policies to create effective economic incentives for change and using our own consumer behaviour to drive that change as well.

So we shouldn’t get diverted into taking excessive risk or sacrificing large amounts of potential return for uncertain benefit. I’ll return to this more in a separate article. But that doesn’t mean we should do nothing. Our actions — whether it’s where we buy or where we invest — send signals. And these signals add to the growing volume of opinion that we need companies and governments to act to avert climate catastrophe.

And act now.